Albert Paley has been known as a sculptor since 1974 when he won national acclaim for creating the forged gates of the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery. But he began his career as an art jeweler.

Albert Paley has been known as a sculptor since 1974 when he won national acclaim for creating the forged gates of the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery. But he began his career as an art jeweler.

He was studying sculpture at Tyler School of Art in the early sixties when he took a jewelry course with Stanley Lechtzin, head of the school’s jewelry department. Lecthzin, who was pioneering the use of electroforming in art jewelry at the time, became Paley’s mentor and the two of them helped make the Philadelphia area an apex of the Craft Movement over the next decade.

Paley juggled small sculpture and jewelry for a few years but sculpture appeared to be winning by the mid-seventies, judging by the body armor he was making then. This formidable pendant, for example, measures 19 inches long, extending the entire length of a woman’s torso. Many of his neckpieces were similarly phallic.

“I was approaching jewelry as an art form, not a fashion accessory. The scale related to the human form,” Paley told me a couple years ago. “My jewelry was not a flat, graphic statement like a lot of jewelry is. It was three-dimensional, like the human body. The concept was bodily ornamentation.”

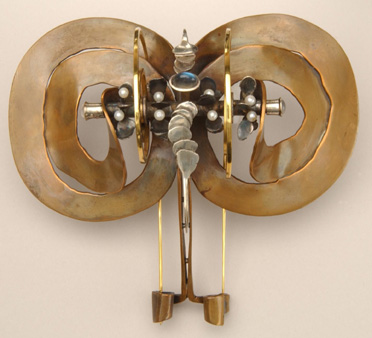

While his pendants were often erotic, his brooches tend to reflect his fascination with Art Nouveau and classical civilization. Paley was fascinated by ancient Etruscan, Roman and Greek jewelry and made a series of fibulas.

Even when his fibulas followed classical form (unlike the one below), they could measure six inches wide – wearable but designed for the artist’s idea of the perfect woman: strong, independent, “with a certain personality that could carry it.” Like much of his jewelry, these oversize brooches hint at the largescale work to come.

He had established his career as a studio jeweler and was teaching goldsmithing. “The whole art process is one, basically, of investigation,” he says. “At the time I was involved with the exploration of materials like gold, silver, copper, bronze. I was using iron, at first, as a toolmaker. I would make stakes, hammers and chisels to form the jewelry. Then I started looking at iron in an art context.”

In 1974, still working as a jewelry artist, he submitted drawings for the Portal Gates of the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery and, to his surprise, won the commission. It changed his life.

“In hindsight, I never thought it would change my career in the way that it did but because of the reputation of the Renwick, I received other commissions that brought me into the context of architecture,” says Paley, who was 28 at the time. He soon discovered that large-scale architectural work did not mix well with jewelry-making. “Sitting at a goldsmith’s bench and swinging a hammer are totally different things.”

He was also frustrated with the art jewelry movement. “The field had become overcrowded and derivative,” he says.

Paley renounced jewelry soon after, retrieving pieces from various galleries and locking them away. Three decades later, the jewelry he made in the sixties and seventies sells at auction for prices that would have made him a happy man in his jewelry-making days. A brooch sold at Ragos Arts and Auction Center in 2006 for $30,000.

I visited Paley’s bustling, cavernous studio in the mid-nineties, on assignment for Art & Antiques magazine. Earlier this year, Paley moved his Rochester studio into an even bigger space to accommodate the construction of 100-foot sculptures – like the one at National Harbor, near Washington D.C. – and the dozen or more men who help construct them.

He wouldn’t trade these ambitious projects but sometimes misses the intimacy and independence of the goldmsith’s life. When Helen Drutt’s avant garde jewelry collection was exhibited at the Houston Museum of Fine Art, including four pieces by Paley, she told me Paley would never make jewelry again. But he has always defied expectations – even his own.

A couple years ago, he got a commission for a pendant and quietly dusted off his jewelry tools to make it. “When I was doing the jewelry nobody thought I would ever not do it, and once I started doing ironwork nobody thought I would ever make jewelry again,” he says. “I guess this’ll keep ’em guessing.”

Related Posts

Alexander Calder’s jewelry: going mobile

Jewelry by famous artists: Picasso, Ernst, Braque

Salvador Dalí: bejeweled surrealism

René Lalique: ultimate art jeweler

Related Product (Buying from links on this site does not cost you any extra but it puts a few cents toward the maintenance of this site.)