While musicians and poets were rebelling against the status quo in Greenwich Village in the mid-20th century, metalsmiths like Art Smith and Sam Kramer were setting up studios there and reinventing modern jewelry.

Many people picture Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac or Bob Dylan when they think of Greenwich Village in its artistic heyday. Mad Men fans got a peek at that bohemian scene, circa 1960s, through Midge, Donald Draper’s beatnik lover.

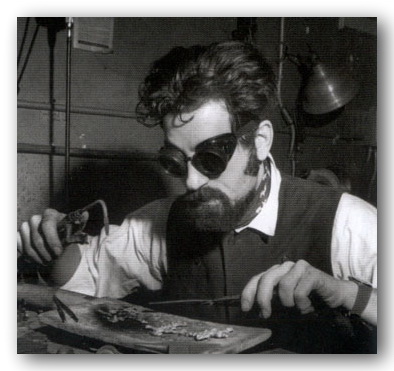

Jewelry artist Sam Kramer (1913-1964) fit right in. Setting up shop in Greenwich Village in 1939, Kramer epitomized the eccentric artist, sometimes opening his store in the morning still wearing his pajamas.

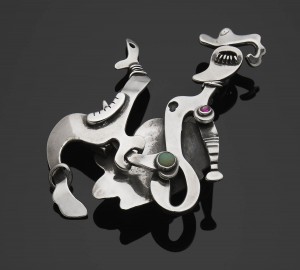

Kramer’s shop was itself a study in Surrealism, from a hand-shaped front door handle customers had to “shake” to enter, to oversized jewelry with hallucinogenic figures and Dali-esque body parts.

Sam Kramer described himself as a rock hound and was known to incorporate fossils, meteorites, coral, rhinoceros tusks, even glass taxidermy eyes in his jewelry. He once attempted to make a bracelet from his wife’s recently-removed gallstones.

Audrey Friedman, owner of the Primavera Gallery, remembers exploring these shops in the 1950s, when flower and animal motifs were all the rage in fine jewelry. “I used to hang around down in the Village and I remember a lot of jewelers making things with glass eyeballs, things that were kind of surreal,” Friedman says. “You figure, if the style was birds and flowers, than to do something with eyeballs and lips would have been really different, very countercultural.”

“A lot of studio jewelers had their studios in the Village then,” she recalls. “One place on MacDougal street – I forget who the guy was – had a doorknob with a big glass eyeball. I remember buying a piece of jewelry there and after I got it home, I decided it was godawful ugly and tried to rework it, unsuccessfully.”

It was easy to get caught up in the creative spirit though. “There was the idea then of doing something that was a little bit outrageous,” Friedman says. Those early forays into the Village left her with a taste for wearable surrealism and led to her own collection of Salvador Dali jewels, including the famous Ruby Lips brooch, which has been exhibited in museums around the world.

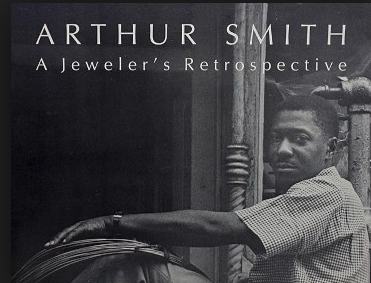

Not far from Kramer’s shop was the studio of Art Smith (1917-1982), another important jewelry artist of the forties. Smith’s jewelry also ran large but where Kramer’s was figural and humorous, Smith’s was abstract and dramatic. Daphne Farago was obviously enamored with Smith’s jewelry. There are 15 works by him in the 650-piece collection she donated to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in 2005.

An African American who grew up in New York City, Smith took his inspiration from African tribal art and costume. He worked as a costume designer for several black dance companies in New York, which allowed him to experiment with his favorite theme: movement.

“His work was very large and sculptural but designed to sit well and move with the body,” says Kelly L’Ecuyer, curator of decorative arts and sculpture at Boston MFA, who helped organize an exhibit of Farago’s collection in 2007. “His primary concern was the relationship with the body.”

“Work by Art Smith and Sam Kramer have, at times, a raw appearance, but in terms of the art world, they were at the cutting edge—the equivalent of a painter or sculptor,” says Yvonne Markowitz, the museum’s curator of jewelry.

Part of the raw quality of this early work came from lack of available jewelry training in the U.S. at the time. Kramer took a jewelry-making course in southern California taught by a ceramicist and Smith apprenticed with a jeweler. Other jewelry artists of their day learned casting from dentists and forging by hanging out at dockyards.

While Smith’s jewelry was more graceful in form, Kramer did a lot to promote the use of found objects in jewelry. When Farago’s collection was exhibited in 2007, you could see the evolution from Sam Kramer’s 1950 cuff bracelet set with taxidermy eyeball to necklaces made a half century later from wooden rulers (by Kiff Slemmons) and crack viles (by Jan Yeager).

Jewelry by contemporary jewelry artist Bruce Metcalf was also shown, looking every bit as trippy and Surrealistic as the early work of Sam Kramer. Kramer would have appreciated the zany direction studio jewelry took after his death in 1964.

For more on this era, I recommend these books: Messengers of Modernism: American Studio Jewelry 1940-1960 or Form & Function: American Modernist Jewelry, 1940-1970

Maker’s marks courtesy of Modern Silver’s excellent index of maker’s marks used by mid-century American jewelers

For more work by Sam Kramer, Art Smith, and other mid-century modernist studio jewelers, visit The Dukoff Collection

Related posts:

Salvador Dali: bejeweled surrealism

Alexander Calder’s jewelry: going mobile

Related products: