Continued from Jewelry by Picasso: the secret stash of Dora Maar, part 2

Gloria Lieberman, director of fine jewelry at Skinners in Boston, had not seen the jewelry Picasso made for Dora Maar when we spoke before the 1998 auction, though she has sold plenty of the jewelry he designed with François Hugo in the ’50s and ’60s. “I don’t consider Picasso a jewelry maker,” she said. “The body of his work with Hugo is small elements of his larger works, executed as jewelry by someone else. This jewelry sounds similar but more personal. I think it will interest an art collector looking for something personal.”

Gloria Lieberman, director of fine jewelry at Skinners in Boston, had not seen the jewelry Picasso made for Dora Maar when we spoke before the 1998 auction, though she has sold plenty of the jewelry he designed with François Hugo in the ’50s and ’60s. “I don’t consider Picasso a jewelry maker,” she said. “The body of his work with Hugo is small elements of his larger works, executed as jewelry by someone else. This jewelry sounds similar but more personal. I think it will interest an art collector looking for something personal.”

“If a collector comes in with a wife and fails to get a painting, these are cheaper. It will be a way to compensate,” Marc Blondeau told me with a laugh some time before the auction. Blondeau was founding director of Sotheby’s Paris and helped catalog the items found in Maar’s apartment after her death.

Their predictions proved correct. Buyers tended to be art collectors who “followed Modern Art into the domain of jewelry,” jewelry expert Philippe Serret, who valued the jewelry for auction, told me at the time. “Most weren’t especially interested in the jewelry market but were buying Picasso’s work in the form of jewelry.”

Serret did not believe the success of the sale would affect the value of the jewelry Picasso designed later with Hugo. The latter “was produced as limited editions; it was not created by the hand of the artist,” Serret said. “I consider it totally separate from the jewelry made for Dora Maar.”

Most of that jewelry dates from 1936 to 1939, the first three years of the affair between Picasso and Maar. The only written reference to the jewelry that the Paris experts could find appears in the biography Picasso and Dora, written by James Lord, an American who lived in Paris after World War II and became friends of both.

According to Lord, the first piece of jewelry Picasso made for Maar was a compensation for a lost gold and agate ring with a cabochon ruby for which she had persuaded him to trade a watercolor. During a stroll along the Pont Neuf, the couple got into an argument. “He reproached her for having prevailed on him to give a work of art in exchange for a bauble,” Lord writes, “where upon Dora took the ring from her finger and threw it into the Seine, silencing her lover. She later regretted having been so impulsive. A few months afterwards, the riverbed at that spot was being dredged, and for several days Dora haunted the spot, in hopes of recovering her ring. But it was lost for good. And through Picasso’s fault. . . . So she kept at him until he created a ring of his own design for her.”

It seems Lord was unaware of the many other pieces of jewelry Picasso made for Maar. At one point she showed Lord a silver cigarette lighter engraved with her portrait, one of the double-profiles typical of Picasso in the late ’30s. Dora called it “one of her most treasured possessions.” When he replied that it was beautiful, she said: “That’s not it’s only value.”

“Picasso had never been a great giver of gifts,” Lord writes. “Of paintings and drawings, yes, but those, though precious, were things that poured inevitably from his fingers and required no demonstrative consideration of the . . . recipient.”

“I never asked him for anything,” Maar asserted. “And I prize the cigarette lighter because it cost him at least a visit to the Place Vendome.” Apparently, the framed-portrait jewelry required at least that much trouble, since Picasso used premade jewelry.

Lord describes a mahogany bookcase with glass doors that Maar called her “private museum.” In it were objects made by Picasso, including a bronze hand and bust of Dora, matchboxes with drawings on them, several large books (illustrated by Picasso) and a “Picassian menagerie of animals and birds made of wood, paper, plaster, metal” – no doubt among the objects auctioned that year.

“He doesn’t know how to stop making things,” she told Lord when he first saw this collection in 1953. “It must be terrible for him. Of course, it’s terrible for us as well.”

When Picasso left her for Françoise Gilot, Maar was distraught and suffered what some biographers describe as a nervous breakdown. Gilot bore Picasso two children, including Paloma, who became a jewelry designer herself. Yet some of the jewelry found in Maar’s apartment proves she and Picasso remained in contact long after their breakup. A couple pieces were presented by Picasso on her birthday in the 1950s, containing portraits made of her in the ’30s.

Picasso had many lovers, but most have died. If any more of his handmade jewelry exists, it’s probably in the possession of Gilot, who is still living in France. In 1964, she published My Life with Picasso, an account of her years with the artist, which inspired the 1996 movie Surviving Picasso. No mention was made of jewelry made for her by the artist.

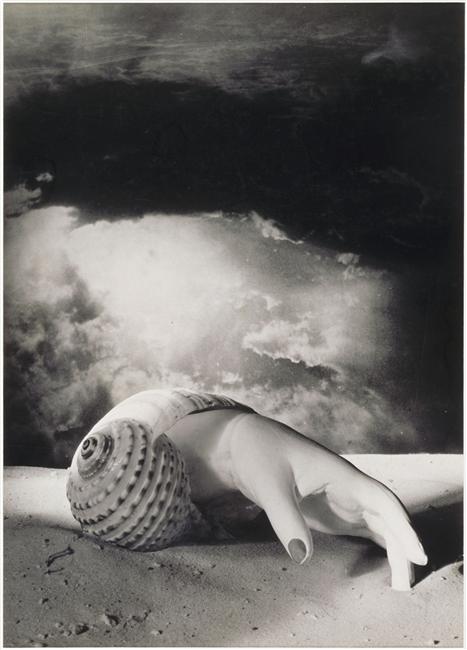

Judging from the contents of the estate and from Lord’s biography, there was a lot more to Maar than the discarded “weeping woman” of the famous portraits who is often portrayed as pining away for decades in a shrine to her ex-lover. The striking photographs in her estate prove how she earned her reputation as a talented photographer among the Surrealists. When she met Picasso, she was running with the likes of André Breton and Man Ray. Picasso influenced her to begin painting, which she continued to do in her studio/apartment until her death – but it was her connection to her celebrity lover that made her famous.

Despite the mass of Picassos in her possession when she died, Maar sold several of his works over the years and was known as a shrewd negotiator. In the 1950s, Lord recalls her asking: “How much do you think they’re worth, the Picassos on my walls?”

“Half a million dollars,” he guessed. “Maybe more.”

“Much more,” she said, gesturing emphatically with her cigarette holder, scattering ash. “And I’ll tell you why. Because they’re mine. On the walls of a gallery maybe, they’re worth only half a million. On the walls of Picasso’s mistress, they’re worth a premium, the premium of history.”

No one is arguing that point now. Five hundred people crowded into a room in Paris in 1998, a few months after Maar’s death, hoping to capture a little of that history. The art, mementos, and surprising cache of jewelry brought $37 million.

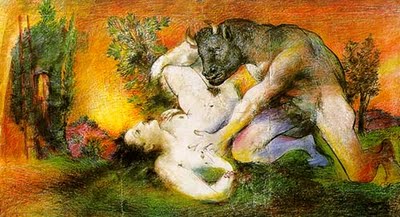

And if there were any doubts as to the depth and complexity of Picasso’s feelings for Maar, her estate did much to dispel them. “The whole lesson of this sale was that the image we had of Dora as the tortured one Picasso dumped – it just can’t be true,” said Amy Sloane-Pinel who helped promote the sale from her Paris office. “The image of Dora and the Minotaur was monumental and incredibly heated sexually,” she adds, referring to a colored drawing in the sale of a nude Maar being overwhelmed by a man with the head of a bull, an image Picasso often used to depict himself. “Just to look at it, it’s hard to believe she didn’t count for him. That this was a two-way relationship is obvious and has become clear in this body of work.

“The big surprise of this collection was the level of intimacy and affection and intellectual respect he obviously had for her which he didn’t have with his other muses. The perpetual question is: was he meanest to the one he loved most? And the answer is theirs. It will go to the grave with them.”

Related product: (Purchasing through links on this site does not cost you more, but it does put a few pennies toward the continuation of this blog.)