Few people have done more to push contemporary studio art jewelry forward than Helen Drutt. She was teaching craft history at art schools in Philadelphia just as the Studio Craft Movement was taking off there in the 1960s. Albert Paley was studying studio jewelry with Stanley Lechtzin at Tyler School of Art, Olaf Skoogfors was teaching it at the Philadelphia College of Art, and George Nakashima and Wharton Esherick were reinventing woodworking nearby.

Drutt became an advocate, then a dealer, of studio craft, and ultimately one of the foremost experts on contemporary studio jewelry. Her reach eventually extended around the world. She was one of the first to champion Paley, then German artist Claus Bury. You can find her jewelry collection, produced between 1960 and 2000, at the Houston Museum of Fine Art.

But don’t call her a collector.

I took this photo (left) at the opening ceremony of the Barnes Foundation last year, after the controversial relocation (made famous in The Art of the Steal) of Philadelphia’s most famous single-owner art collection from Main Line suburbia to its spiffy new digs on the Ben Franklin Parkway. Like Drutt, Albert Barnes was a local art aficionado who went against the grain, saw himself primarily as an educator and advocate of then-radical contemporary art (Impressionism and Modernism mainly). So it seemed fitting to find Helen there. She is, in many ways, a worthy successor to Barnes.

I spotted her necklace first and ran over when I saw who was wearing it. The mayor was about to speak, so there wasn’t much time (thus the blur). As I lifted my camera, she raised a bangle-covered arm and gently touched the brass spirals Calder had once hammered. “This is not within my genre,” she said, “but it seemed appropriate for the occasion.”

I nodded. I’d spent hours talking to her about this five years earlier and knew that, while she loves Calder’s jewelry, it predates her own specific interest. No collector I’ve ever met has more exacting parameters than Helen Drutt – not that she’s a collector, of course.

In 2007, when the Houston Museum of Fine Art announced it had acquired Drutt’s collection and was putting it on display in Ornament as Art: Avant-Garde Jewelry from the Helen Williams Drutt Collection, I was sent to interview her at her turn-of-the-century townhouse in Center City Philadelphia. Her home was cluttered, bohemian, filled to the brim with bold, colorful contemporary art.

She handed me a book of Irish verse to read as she dealt with a flood upstairs with her assistant, but I just sat and looked around in awe. Ceramic art covered her grand piano and every surface of the room, including the mantel, windowsills, and radiator tops. She had required me to remove my shoes before walking on her Oriental carpets. A large abstract silk tapestry covered one wall, beside an 8-foot tall ceramic figure and big potted orchids.

I had heard Drutt speak at the first SOFA New York show in 1998 (last year was its last), wearing her trademark hat and splashy art jewelry, but I’d never met her. I knew enough to be intimidated and she was a bit intimidating. It was important to her that I get this right and she didn’t hesitate to interrupt and correct me. She had just handed over more than 800 pieces of studio jewelry to the Houston museum – including pivotal work by Paley, Lechtzin, Skoogfors, Joyce Scott, Wendy Ramshaw, Helen Shirk, Bruce Metcalf, and studio jewelers throughout Europe – and wanted to make it clear she was not just another collector. She helped other people build collections. She was an academic, an educator and a gallerist, an advocate of contemporary craft.

Albert Paley also spoke at that SOFA show. By then, Paley had moved on from jewelry to sculpture and from Philadelphia to Rochester, but was still friends with Drutt. They were introduced by Paley’s instructor and mentor at Tyler, Stanley Lechtzin. It was Drutt who helped make Paley famous as a studio jeweler, but it was Lechtzin who got Drutt interested in studio jewelry in the first place.

Looking around at her art-filled living room, I asked her why she had settled on art jewelry all those years ago.

Obviously, you deal with all kinds of art and craft. How is that studio jewelry became your legacy?

Helen Drutt: When I first saw the work of Stanley Lechtzin [in the late 1960s], I’d never seen jewelry like that. It wasn’t a painting and it wasn’t a sculpture, but it had the same aesthetic. It wasn’t like a string of pearls, didn’t have that homogenized look. It wasn’t just something to be worn on a dress or sweater. Something was really happening. Ideas were pulsating in the work.

I didn’t know that existed. I was intrigued by it. I didn’t know a brooch could have the same qualities as a Nakashima or a Wharton Esherick. Suddenly, I was faced with the fact that jewelry was being made that had the same critical and aesthetic base.

I couldn’t sleep the night after I saw the first Lechtzin. I couldn’t stop thinking about it. How come I didn’t know about this? How could this be happening in my city and I had no idea it was happening? Why hadn’t somebody told me? If they had, I probably would have been on the steps of Sam Kramer and Art Smith’s studios in the ’40s and ’50s. I would have been up in the Village looking at it the way I was with Nakashima and Esherick and Phillip Lloyd Powell. Had I known, I would have been there, asking questions.

I was also the crafts member of that emerging society now called Collab. When I went to the meetings, if I wanted to talk about the crafts, I couldn’t carry in a Nakashima table or a big ceramic pot, but I could wear a brooch that evoked the same information, or acted as a catalyst. It was an easy way to do it. The jewelry was no different from the furniture or other crafts. It was just a vehicle that was more affordable and more portable.

What sets your collection apart from other 20th-century studio jewelry collections, like Daphne Farago’s at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts?

HD: Her collection is much more universal than mine, in the sense that it dates from World War II studio metalsmiths like Sam Kramer and Art Smith into Modernism, then Calder. I sold Daphne a few pieces. In fact, I had more Art Smiths in my possession in the ‘ 70s than anyone I knew. But I had no connection to him. For me, the collection had to do with my discourse with the artists, people I knew, had spoken to, whose ideas I could share.

I could appreciate Smith and Kramer and Margaret De Patta. Their work was fabulous. They were great artists. But I never sat down and talked with them. It was an academic thing for me. My collection starts at 1960. What I was interested in was that moment of the revolution, that moment in which social jewelry and studio jewelry took off into a different sensibility. I was interested in that pivotal period between 1960 and 1964, between the first international exhibition of modern jewelry at Goldsmiths’ Hall in London and the one [Internationale Ausstellung: Schmuck Jewellery Bijoux at the Hessisches Landesmuseum] that opened in Germany in 1964. That’s what really grabbed me.

I’m not a competitive gallerist. My motto has always been that I’m trying to help develop people.

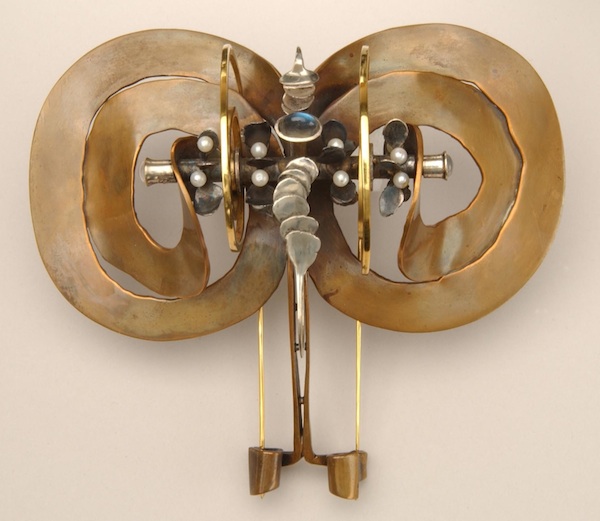

Albert Paley was one of those people. He credits you with helping him get established. You were buying and selling his jewelry before most people had ever heard of him. You have some amazing pieces by him in your collection. They’re very big and very bold. Did you actually wear them at the time?

HD: There’s hardly a piece he made that I didn’t wear. I remember the brooch I wore at the unveiling of the Renwick Gates at the Smithsonian [Paley’s big break into full-scale sculpture] and what I was wearing with it – a sage green plaid Pierre Cardin cape and skirt with a white turtleneck sweater. I remember wearing an Albert Paley brooch to the 1976 Bicentennial dinner at the art museum. Diana Vreeland was looking at me and couldn’t place my dress or my pin. It was a black gown with long sleeves, small ruffles at the cuff, and a huge tutu skirt. She could identify who was wearing what but I wasn’t wearing anything that she could identify.

As a collector, do you…

HD: I’m not a collector. I’m an educator. My main focus is not the acquisition of work, I only began to acquire it when nobody else wanted it. There’s no doubt about that.

You’ve said you sold things at times without taking a commission because the artist needed the money more than you did. Do you see what you were doing as a service to the artists?

HD: No, it had nothing to do with the artist. It had to do with history. I was holding history. I was making certain that I didn’t lose sight of the ideas that were emerging during my lifetime. And I never acquired a piece that somebody else wanted first. I always waited to see if somebody else wanted it, sometimes for years. Normally they would stake their claim on it.

I had a tendency to stick with a group of people and try to go in depth, if I could. It wasn’t always possible because I didn’t have the funds. This was done at great sacrifice. I never owned a car. Other collectors were economically able to do whatever they wanted. I wasn’t, but I went out on a limb a lot more.

It was pretty funny actually. When I knew I wanted a particular piece it was schh, schh, schh… [She closed her eyes and tapped on her head as if it were a calculator.] But I never did that without offering it first to somebody else.

Related posts:

Albert Paley: bodily ornamentation

Art Smith & Sam Kramer: heyday of modernist jewelry

Handcrafted wood jewelry boxes

Best crafts shows in the U.S. in 2013

Related products: