The fan represents a tradition that dates to ancient civilization, certainly in Asia. By the 19th century, fans were multifunctional requirements for the well-dressed woman throughout the Western world.

“They were handheld jewel-like objects used to emphasize a gesture and, nominally, to keep you cool at a time when air was not necessarily moving in a crowded room – especially after any exertion,” says Phillys Magidson, curator of decorative arts at the Museum of the City of New York, who helped chose the many decadent fans on display in Gilded New York.

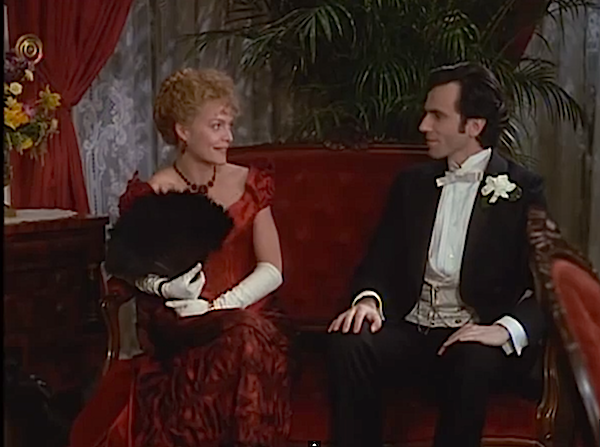

After a whirl around the dance floor wearing the heavy, boned contraptions of the day, a fan was something a girl could hide behind while blowing a little air at that sweaty brow. “During a ball,” Magidson says, “it was not really appropriate for a woman to show color in her face or to sweat.”

Not quite as effective as central air? But beautifully crafted, lovely to look at, and the feathers probably made them fun to swish around. Most of the fans in Gilded New York have at least some, and a couple are made entirely of feathers.

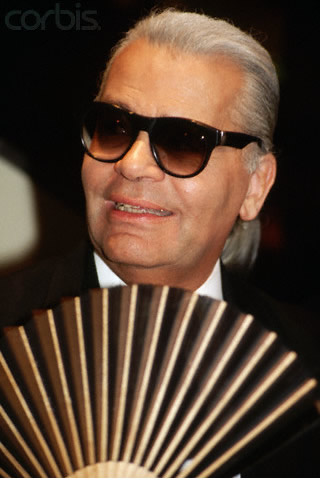

Many legends about fan usage seem to hold true even today – including explanations offered for Karl Lagerfeld’s copious use of this accessory: as a fashion statement, a device for camouflage and cooling, and occasionally to swat people like flies. Designer Julien Macdonald, who went to work for Chanel at age 21, told Vogue that Lagerfeld used his fan to taunt and sometimes hit him when he acted up.

A profile in New York magazine speculates that Lagerfeld, now 80, used his fans to hide and cool himself when he was feeling fat – he lost 90 pounds not long ago – and as part of his image as last of the Old World couturiers: “His look is an extremely conscious metaphor for his philosophy of fashion and life: Here, watch as I bring together the old, in my tall eighteenth-century collar and bizarre powdered hair, with the new, as seen in my ponytail and $2,500 Agatha leather pants.”

Lagerfeld was merely rediscovering the many uses of one of fashion’s oldest multipurpose accessories. Whether or not it became a weapon, the fan was pretty effective for non-verbal communication. “It was always used as a means of flirtation and to punctuate a point in conversation, something to do rather than sitting with your hands folded,” Magidson says. “Flirting was part of that.”

Lagerfeld was merely rediscovering the many uses of one of fashion’s oldest multipurpose accessories. Whether or not it became a weapon, the fan was pretty effective for non-verbal communication. “It was always used as a means of flirtation and to punctuate a point in conversation, something to do rather than sitting with your hands folded,” Magidson says. “Flirting was part of that.”

So was spying. Many fans, dating to the 18th century, had little mirrors mounted on at least one of the guards so a lady could get a look behind her without turning her head. “This would have come in handy on various occasions,” Magidson says.

By the late 19th century, fans were as much a status symbol as jewelry itself. “They were statements about money and how much you spent on this extraordinarily beautiful, extravagant thing,” Magidson says. The most prominent fan makers of the Gilded Age were located in Paris. When wealthy women went on their regular visits to the Paris ateliers, they would pick up a fan or two to go with their ensembles.

Fans were often given as wedding presents, often monogrammed with gold and sometimes set with diamonds. “They were very extravagant,” Magidson says. “And many had beautiful presentation boxes too. At Tiffany, wedding fans were sold in white satin-covered boxes and with a gold stamp within the lid – very impressive.”

By the Deco era, use of fans had faded, but their elegant echo lingered in the jewelry women wore. This one by Cartier is an example of the Egyptian-style brooches popular in the early 1920s.

They continue to be a common motif in jewels, despite the fact that most of us have abandoned the fan as fashion accessory and device for hiding, cooling, flirting and spying – with the exception of Lagerfeld, of course. (He can get away with anything.)

Related products