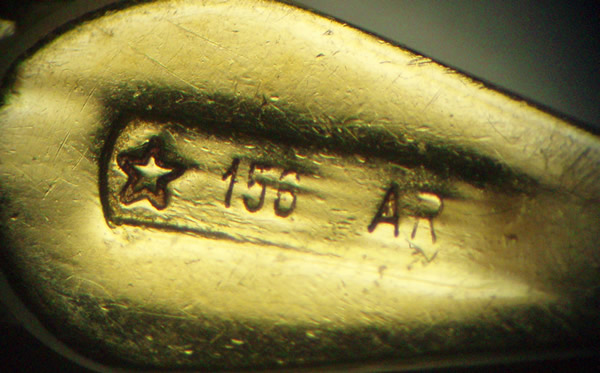

Buying antique or vintage jewelry means first figuring out what it is, where and when it was made, and by whom. That’s why the first thing an experienced buyer will do is hold a piece up to a loupe and examine it for hallmarks. If jewelry has hallmarks and they appear authentic, identifying its value is a whole lot easier.

But many countries – including the U.S. – do not have an official hallmarking system and the hallmarks of one country can vary dramatically from another. How does a budding collector begin to unravel this puzzle?

But many countries – including the U.S. – do not have an official hallmarking system and the hallmarks of one country can vary dramatically from another. How does a budding collector begin to unravel this puzzle?

A trusted dealer can help but if you want to learn to identify jewelry on your own, you’ll need a good guide. There are a few books on the market, but if you want the ultimate, illustrated reference book, be prepared to shell out a couple hundred bucks for World Hallmarks, Volume I: Europe, 19th to 21st Centuries. As co-author Danusia Niklewicz puts it, “This book will pay for itself with one correctly identified piece.”

I recently spoke to Niklewicz and William Whetstone, who compiled this tome with fellow appraiser Lindy Matula, about the basics of hallmark identification.

Is it common for people to confuse a maker’s mark with a hallmark?

Danusia Niklewicz: Yes, especially in the U.S. where we don’t hallmark goods. On our website people can send in questions about hallmarks and many times we receive maker’s marks instead of hallmarks. People think any maker’s mark is a hallmark and that becomes a problem. Maker’s marks aren’t nearly as well documented as hallmarks.

Many countries don’t offer lists of registered makers or their marks. Even in the U.S. and Canada, there is no requirement to register one’s mark. As a result, there is nowhere to research the identity of a signature or mark. You will only find hallmarks on jewelry made in countries that have laws that require independent testing of metal fineness and that document their makers marks with an official stamp – a government stamp or an independent lab stamp – indicating the results of such testing.

William Whetstone: In many places, especially Europe, it’s required that a maker register their mark at a hallmarking or assaying office so it can be tracked. In most European countries, a secondary system is set up where the assay office tests the pieces and puts their stamps on it to indicate that it was verified by an independent body. It’s similar to gem certification. Most people buying an expensive diamond today want a certificate issued by an independent organization like the GIA. Just like these certified diamonds that are laser-inscribed on the girdle of the diamond with the cert number, a hallmarked item is marked with the results of the testing.

So what kind of assurance am I getting with a maker’s mark?

Whetstone: A maker’s mark can be the manufacturer, the company that sponsored the piece to be made, or the individual craftsman. In any case, whoever is marked on the piece takes the responsibility for it. In countries where they don’t even mark their pieces, the importer becomes the responsible party. Really, a hallmark is about the most important means of consumer protection within the precious metals. In other words, if you’re a maker and you stamp something 18kt, you take responsibility. You’re guaranteeing that it’s 18kt.

Niklewicz: In most European countries, including France and Great Britain, an item is not legal for sale without a hallmark. Germany doesn’t have hallmarking, but it’s the exception. A few countries, like Austria and Norway, have optional hallmarking. Italy doesn’t require hallmarking but it has better registration of the maker, a specific number, so what you see as an Italian mark was placed there by the maker. It’s a little more formal than any other maker’s voluntary marking.

Does that mean I’m safe buying jewelry made in Italy?

Whetstone: Not necessarily. I think it’s easy to recognize Italian marks but you don’t have the same protection or guarantee unless an item is hallmarked. There was a notoriously famous chain that marked their jewelry 18kt on one side and “Italy” on the other. “Italy” is not a guarantee. So you find the 18kt gold chain you bought is only 14kt gold. Who do you hold responsible? The merchant you bought it from can say, “It’s not my fault. It doesn’t have my trademark on it.” This goes on all the time. Under-karating is rampant in North America.

It’s caveat emptor here?

Whetstone: We were talking to assay masters at a conference in Geneva and they privately say they laugh at the consumer protection system within the U.S. because there is no policing of this.

Niklewicz: The U.S. is missing out on a huge European market because we don’t have the standards they demand. They consider our products generally inferior.

Whetstone: Tiffany & Co. sends jewelry to London to have it hallmarked so they can sell it on the European market. Most jewelry makers don’t realize how fast and inexpensive it is to have jewelry hallmarked now, given modern technology. If you’re selling something for $1,000 or more and it only costs $10 to get it hallmarked, that’s a worthwhile investment. You can also get volume discounts.

What can I learn from hallmarks if I’m collecting estate or antique jewelry made in France or other parts of Europe?

Whetstone: In some countries, hallmarks can tell you what city and what year a piece was made. At the very least, they allow you to figure out the country of origin and that’s really important. Somebody recently sent me a picture of an Art Deco piece they thought was French. It wasn’t. It was Egyptian. It was extremely well made. There were a lot of talented craftsmen in Egypt during 1920s who came from France and England and were doing very fine work. But this person thought the piece came from France. Does it make a difference in value if a piece is French Art Deco instead of Eyptian Art Deco? Yes, a big difference.

Does understanding hallmarks mean I can buy antique jewelry on eBay – or is it best to avoid that?

Whetstone: eBay is a viable market, providing you’ve done your research to make sure what you’re looking at is correct. I buy on eBay. One problem with buying on eBay is that I consistently see stuff that is just wrong. I informed a seller recently that something advertised as “made in the 1700s” was actually made in the 1930s in Czechoslovakia. In many cases, mistakes like that are innocent and they thank me and take it down. But that is why you have to read and do your homework before buying.

Want to learn more about evaluating old jewelry? Check out Bill and Danusia’s book on Europe hallmarks. [Note: As of 2025, both volumes are out of print. Best prices I’m finding for this book are on eBay.]

Other recommended books on jewelry hallmarks & identification

Jackson’s Hallmarks, Pocket Edition: English, Scottish, Irish Silver Hallmarks from 1300 to Present Day

Illustrated Guide to Jewelry Appraising: Antique, Period and Modern

American Jewelry Manufacturers

The Little Book of Mexican Silver Trade and Hallmarks

Hallmarks of the Southwest: Who Made it?

Reassessing Hallmarks of Native Southwest Jewelry

Images courtesy Hallmark Research Institute

This post contains affiliate links.