Who needs fertility treatments when you can wear jewelry instead – particularly, jewelry like this?

Among the earliest treasures on display right now at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts is this Nubian pendant of gold and rock crystal made around 740 B.C. with the golden head of Hathor, a goddess beloved in ancient Nubia and associated with love, beauty and music. She was believed to offer protection to women throughout their adult lives. Inside the carved crystal sphere is a cylindrical gold amulet case, worn exclusively by women, probably to enhance fertility.

Many of the 71 pieces in Jewels, Gems, and Treasures: Ancient to Modern (through November 25, 2012) were made by men, but it was mainly women who wore them and sometimes with serious purpose.

Thanks mainly to jewelry-loving patron Susan B. Kaplan, the Boston MFA is the first major art museum to get not only a large gallery (700 square feet) devoted entirely to rotating jewelry exhibitions, but a dedicated jewelry curator.

Markowitz has been an ancient art specialist at the museum since 1998 and a long-established jewelry historian. She now finds herself in a jewelry lover’s hog heaven, with an almost endless treasure trove– about 11,000 pieces of jewelry in the permanent collection – to sift through, pulling out themes and telling stories of human history through the ornament people made and wore. The museum’s jewelry collection spans 6,000 years of civilization, from ancient to modern avant garde.

As her first theme, Markowitz decided to focus on the way materials evolved in jewelry over the centuries. What she came up with will thrill anyone who loves rare and unusual gems and jewels, and the mirror they hold up to bygone eras. “It’s a look at the way different cultures at different times have prized or regarded certain materials as precious,” Markowitz explains.

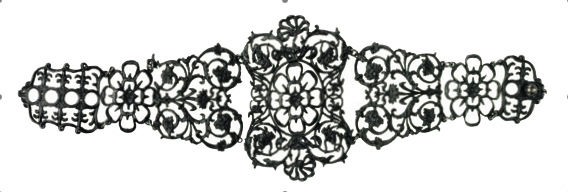

You’ll also find less flashy but no less intricate jewelry made from cast iron in 1850. Berlin iron jewelry first appeared during the Napoleonic wars when women were asked to exchange their precious metal jewels for iron, which they wore as a sort of patriotic badge. These dark, lacquered ornaments – the antithesis of “bling” – caught on as a fashion trend that lasted for decades.

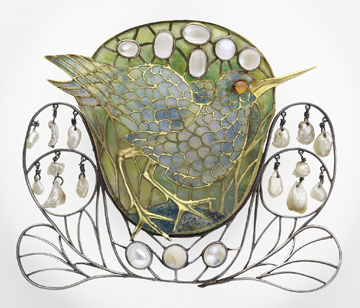

In sharp contrast to these dire black pieces is the colorful, wildly creative art jewelry made at the turn of the twentieth century. Markowitz includes both the elegant French Art Nouveau and a couple fabulous pieces of British Arts and Crafts. One is a hair ornament in the form of a marsh bird made of moonstones, pearls and delicate plique à jour enameling, materials and techniques more closely associated with Lalique and the Parisian Belle Epoque.

Another British jeweler, John Paul Cooper contributes a brooch inspired by medieval and Celtic designs, set with rubies, moonstones, pearls, amethysts and chrysoprase. It took Cooper’s chief craftsman 273 hours to craft this piece, during a period when, according to Markowitz, Cooper “relied on stones rather than representational imagery” for inspiration.

While all the jewelry in the exhibit is fun to admire and ponder, the early work, in many ways, presents the most visceral, uncomplicated pleasure – perhaps because it lacks both the status obsession of the bling and the cynical intellectualism of the avant garde.

“There were a couple things going on in early materials – accessibility, usability, working with the symbolism that was attached to the material,” Markowitz says. “As we go along, we get to our own present age, where the kind of symbolism you find in other cultures, in other times, seems to be replaced by jewelry as an expression of wealth and power.”

Jewels, Gems, and Treasures: Ancient to Modern is open through November 25, 2012, at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.