Lucie Heskett-Brem makes chains, but not as we’ve come to know them. She makes chains Old World-style: hand-crafted, luxury items in high-karat gold. Her chains are carried by galleries like Aaron Faber of New York and Bentley & Skinner of London, jewelers by appointment to the English royal family.

Lucie Heskett-Brem makes chains, but not as we’ve come to know them. She makes chains Old World-style: hand-crafted, luxury items in high-karat gold. Her chains are carried by galleries like Aaron Faber of New York and Bentley & Skinner of London, jewelers by appointment to the English royal family.

Handmade chains are definitely a luxury in today’s world, Heskett-Brem admits. The first chain-making machine was invented in the mid-1700’s and jewelry chainmaking was mechanized a century ago. “It’s not something that needs to be done by hand,” she says.

But like all connoisseurs and studio jewelers who specialize in handmade chains, she is dismissive of the machine-made variety. “Some of those chains they sell from catalogs cost practically nothing,” she says. “They’re made of real gold but if you drop them, they sink to the ground like an autumn leaf.”

Having entered the four-year goldsmithing apprenticeship in her homeland, Switzerland, at the not-so-ripe age (by European standards) of 30, Heskett-Brem quickly found a market for her exquisite old-style chains and now makes them from a studio overlooking Lake Lucerne.

Although she studied a range of jewelry-making techniques, she fell in love with the meditative process of chain-making, linking one piece to the next, and the idea of eternity and human bond that the chain has represented throughout history.

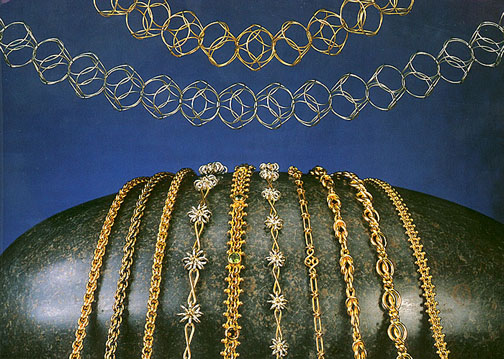

She does not consider herself a modern designer. Her specialty is reinventing the classic chain from eras past, including the very feminine, delicate floral chains of the Victorian era. “My chains are all recognizably made by a woman. I’ve tried to make jewelry for men and it never works out,” she says. “Everything I make, I make because I would wear it.”

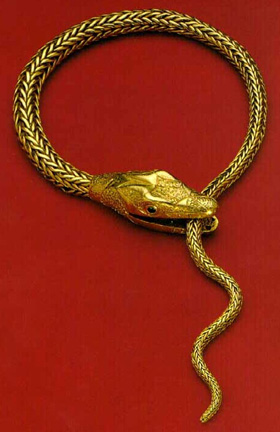

Long before the snake became last year’s fashion craze, Heskett was famous for her snake chains. She has time-traveled as far back as Ancient Egypt for inspiration, when the height of chic was a gold snake wrapped around a slender arm.

Long before the snake became last year’s fashion craze, Heskett was famous for her snake chains. She has time-traveled as far back as Ancient Egypt for inspiration, when the height of chic was a gold snake wrapped around a slender arm.

“The snake chain has always fascinated me,” she says. “When I first saw one, I thought it was done with a continuous wire but I tried this and it doesn’t work. My snake is actually a loop-in-loop chain. A lot of people do it but my specialty is to take it further, as close as possible to being an animal.”

Women have been known to scream when they pick up her snake chains for the first time. Heskett finishes the edges so they’re smooth to the touch and spent months figuring out the optimum balance of density and flexibility so her chains would move like snakes. “You can’t get any denser without losing movement,” she says. “Even the old Egyptian ones—they look the same but they’re not as flexible.”

Heskett examines chains wherever she goes. “I’m happy to report I haven’t seen any that I like better than mine,” she says cheerfully. What makes for a superior chain? “It can be a simple loop-in-loop, the most basic chain there is, maybe twisted flat, which we call an anchor chain, but it needs to have proportion and it needs to flow. Then it has to have some sort of soul. Some chains are all right but they don’t have that.”

Heskett examines chains wherever she goes. “I’m happy to report I haven’t seen any that I like better than mine,” she says cheerfully. What makes for a superior chain? “It can be a simple loop-in-loop, the most basic chain there is, maybe twisted flat, which we call an anchor chain, but it needs to have proportion and it needs to flow. Then it has to have some sort of soul. Some chains are all right but they don’t have that.”

A musician once showed her a chain he had bought for his wife, wanting to know if he had chosen well. “He was a great trumpet player. I looked at the chain and it wasn’t too bad. But I took one of mine off, put it in his hands and said, ‘Look, you’re a musician. Just listen.’ And when he did that, it was clear. The other one was tinny, it just sounded wrong.”

To see Lucie at work, check out the documentary on her site. You can find her at BaselWorld and galleries such as Aaron Faber in NYC.

Related posts:

Birgit Kupke-Peyla: German craftsmanship, California style

Pierre-Yves Paquette: modern mokume gane

Karen Gilbert: science and nature as muse

Related products: