Among the rash of artist/goldsmith collaborations that came out in the sixties and seventies, Man Ray’s jewelry truly stands out. To see what I mean, visit the Picasso to Koons: The Artist as Jeweler exhibit at the Museum of Arts and Design and compare Man Ray’s dramatic sculptural designs to the wall of flat, stamped gold plaques produced at the same time by François Hugo from drawings by Pablo Picasso and Max Ernst. No comparison.

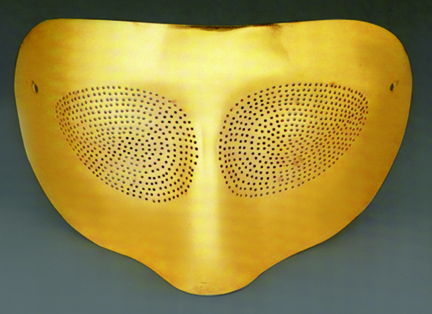

Man Ray’s most famous pieces look a little challenging to wear, but they are superb pieces of craftsmanship – thanks to Gem Montebello, the Italian firm who produced them – and more functional than they appear. His Optic-Topic gold mask, for example, would appear to completely blind the wearer, but if you look closely, you can see a network of tiny drilled holes forming a spiral pattern.

“You see through them as well as with glasses. It’s interesting,” says Diane Venet, who owns this gold mask, one of 100 produced, along with most of the jewelry on display. “Man Ray was always breaking his glasses and he loved to drive fast. So he had a discussion the Giancarlo Montebello about glasses and finally, after a few months, they came up with this.”

I’m not sure if she was implying he wore this while driving fast. If so, he was crazier than we thought. Man Ray was born in Philadelphia in 1890, which means by the time he designed the mask, he was 84. He died in Paris, his adopted home, two years later.

The spiral gold earrings (right) recall the spiral shapes in Man Ray’s work during the early years of the Dada movement and the title, Pendantif-Pendant, reflects his obsession with puns and alliteration. But most people refer to these as “the lampshade earrings,” because the design stemmed from a lampshade Man Ray designed in 1919.

The earrings shown have a conventional post but the originals are 5 1/2 inches long and hung from a wide curve of wire. They weren’t designed to hang directly from the lobe but to loop over the top of the ear. Clever. Man Ray’s idea – or GianCarlo Montebello’s?

Montebello produced this gold and platinum ring, signed and dated by Man Ray, in 1970, around the same time as the earrings. Venet proudly owns one of an edition of twelve.

Man Ray had a couple things going for him that Picasso and Ernst lacked: an extensive background in fashion photography and a genuine interest in creating unique, high-quality, wearable sculpture. He also had Montebello producing his jewelry.

Giancarlo Montebello set up his workshop of highly-skilled craftsmen in Milan, in 1967, inviting a select group of internationally-known artists to contribute designs. Montebello’s team collaborated closely with the artists. Not all artists are household names, at least not in the U.S., but their jewelry definitely stands out above the rest.

You can find other results of these collaborations at the MAD exhibit, including some gorgeous geometric gold pieces designed by sculptor Pol Bury and several whimsical figurative pieces designed by sculptor/painter Niki de Saint-Phalle and executed in colorful enamel by Montebello.

Montebello is still producing artist-made jewelry, evidenced in the exhibit by a lethal-looking spiky gold ring designed by German artist Günther Uecker dated 2011. It was inspired by his Chair with Nails sculpture. (Ouch.)

Montebello, now in his nineties, was planning to attend the exhibition in NYC when I spoke to Venet earlier this month. “I want him to see all this,” she said, waving a hand around the exhibition. “He worked so hard.”

Related posts:

Alexander Calder’s jewelry: going mobile

Salvador Dalí: bejeweled surrealism

Jewelry by Picasso: the secret stash of Dora Maar

Related products: