A ring containing a tiny portrait of Dora Maar sketched by Pablo Picasso and set in a metal composite frame is expected to fetch between $400,000 and $650,000 at Sotheby’s London on June 21st.

UPDATE: The Dora Maar portrait ring sold for $737,311. That’s a whole lot more than it sold for at the 1998 estate sale in Paris following Maar’s death – ten times more, in fact.

You may recognize this ring from the stash of handmade jewelry by Picasso I wrote about here a few years ago. When appraisers came to Maar’s Paris apartment, they discovered a virtual Picasso museum: nearly 60 drawings, 10 paintings worth millions, a number of photographs Maar made of her lover, his work, and their famous friends – she was a gifted art photographer involved in the Surrealist movement – and a slew of mementos, including this ring and several other jewels Picasso had made for his lover decades before.

I reported on the jewelry in that auction for a couple magazines. At the time, the media frenzy was all about the Picasso paintings, expected to sell for millions. Until then, the only jewelry Picasso was known for were the limited-edition gold plaques he sketched in the 1960s, produced by François Hugo, along with those of Max Ernst.

By then, it had become a thing for well-known painters and sculptors to produce wearable spins on their art work via goldsmiths. Man Ray worked with Gem Montebello and Georges Braque with Baron Héger de Lowenfeld. Earlier, in the late 1940s, Dali produced some fabulous jewels with Carlos Alemany. One of the later versions of his “Eye of Time” brooches sold at Sotheby’s last month. And, of course, there was Calder, who didn’t work in precious metals but made about 1,800 pieces of jewelry by his own hand.

Not one of the mid-century jewelry experts I interviewed at the time, however, knew Picasso had made any jewelry by his own hand. But I remembered Dora Maar mentioning this jewelry in Picasso and Dora, a biography written by James Lord, an American who lived in Paris after World War II and became friends with both.

According to Lord, the first piece of jewelry Picasso made for her was a compensation for a lost gold and agate ring with a cabochon ruby for which she had persuaded him to trade a watercolor. During a stroll along the Pont Neuf, the couple got into an argument.

“He reproached her for having prevailed on him to give a work of art in exchange for a bauble,” Lord writes, “where upon Dora took the ring from her finger and threw it into the Seine, silencing her lover. She later regretted having been so impulsive. A few months afterwards, the riverbed at that spot was being dredged, and for several days Dora haunted the spot, in hopes of recovering her ring. But it was lost for good. And through Picasso’s fault. . . . So she kept at him until he created a ring of his own design for her.”

Among the jewels that resulted were brooches, rings, and carved amulets that Picasso made for her during their tumultuous affair in the years leading up to the war.

“The jewelry [and mementos] were all over the place, under beds, in old shoe boxes. She kept it up very zealously as a memorial to Picasso,” Marc Blondeau told me at the time. Blondeau was founding director of Sotheby’s Paris then and helped catalog the items in Maar’s apartment on Rue de Savoie, where she lived during and after her liaison with Picasso.

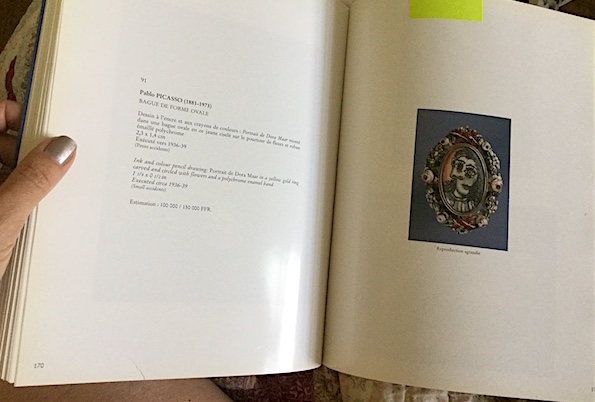

At the 1998 auction, a chrome-metal watch with a brass plaque engraved with a portrait of Maar, estimated for $3,300, sold for about $63,000. A portrait ring in a metal frame of lattice flower work, estimated at about $16,500, sold for almost $108,000. The oval brooch with a colored pencil portrait of Maar fetched nearly $70,000. This month it may sell for ten times that.

“This was a woman who would not accept conventional jewelry,” jewelry expert Philippe Serret told me before the Paris auction, having cataloged the collection in addition to valuing the jewelry. “These were the only kinds of jewels she would accept.” (This was said in French and translated for me at the time.)

Serret estimated the jewelry in 1998 at $3,000-16,000 per piece, which seemed undervalued even then. He insisted afterward that the estimates were not low, simply that there were no precedents for mementos made by Picasso for a lover. “The sentimental value was what drove the prices up,” he told me.

It was Maar’s face, with her intense dark eyes and regal nose, that the artist was painting obsessively when he began distorting images, a style now considered his trademark. Her face appeared over and over during this prolific period for Picasso, looking increasingly tortured as the romance progressed.

“Dora has always been a weeping woman for me,” Picasso would say, according to Pierre Cabanne in Pablo Picasso: His Life and times. ”For years I painted her in tortured forms, not out of sadism or pleasure. . . . It was Dora’s profound reality.”

Most of the jewelry Picasso made for Maar features miniature versions of that famous distorted portrait, mostly sketched in color pencil and mounted in cheap, pre-made metal brooches and rings. Picasso did not do any metalwork, merely inserted his drawings into existing jewelry that ranged from the “yellow metal composite,” as the Sotheby’s catalog describes the ring they’re selling this month, to steel with simulated marcasite. In other words, this was not fine jewelry – but the settings had a quirky charm and, of course, they each held a one-of-a-kind Picasso.

Despite the mass of Picassos still in her possession when she died, Maar sold several of his works over the years and was known as a shrewd negotiator. In the 1950s, Lord recalls her asking: “How much do you think they’re worth, the Picassos on my walls?”

“Half a million dollars,” he guessed. “Maybe more.”

“Much more,” she said, gesturing emphatically with her cigarette holder, scattering ash. “And I’ll tell you why. Because they’re mine. On the walls of a gallery maybe, they’re worth only half a million. On the walls of Picasso’s mistress, they’re worth a premium, the premium of history.”