John Hatleberg has done just about everything imaginable with rare gems: pasting them on naked women, making vegetables out of pearls, counterfeiting diamonds.

When I first met him in the nineties, he was known for turning precious material into objects of art – the kind that got people talking. A skilled lapidary, Hatleberg is equal parts artist, scientist, and showman. At the time, he had just produced a stunningly realistic corn cob from 24k gold, silver, and freshwater pearls.

This piece was inspired by an ancient text claiming the royal gardens of Inca contained, along with real flowers, replicas in precious metal. “They made exact copies of cornfields, with their leaves, stalks, cobs, and blossoms,” it read. “The beard of the cob was gold, and everything else was silver, with the parts melted together.”

This piece was inspired by an ancient text claiming the royal gardens of Inca contained, along with real flowers, replicas in precious metal. “They made exact copies of cornfields, with their leaves, stalks, cobs, and blossoms,” it read. “The beard of the cob was gold, and everything else was silver, with the parts melted together.”

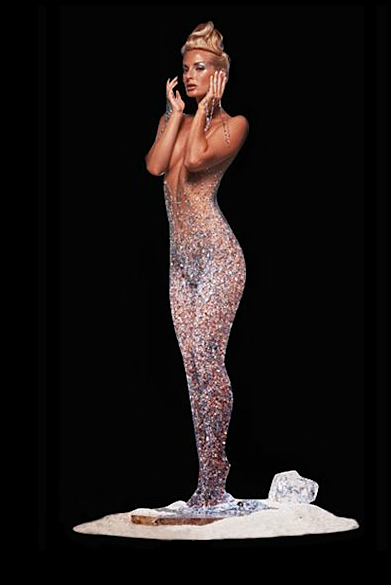

Hatleberg was also known for pasting 30,000 glittering jewels on the body of a nude model. He called this one “She Jewel.”

It was always fun to run into Hatleberg at the Tucson Gem Show. He has a wry sense of humor, and seemed to know everything going on and everyone interesting, from dealers and other (sometimes eccentric) gem carvers to the head of gemology at the Smithsonian Institution. He could talk rocks with all of them.

It was always fun to run into Hatleberg at the Tucson Gem Show. He has a wry sense of humor, and seemed to know everything going on and everyone interesting, from dealers and other (sometimes eccentric) gem carvers to the head of gemology at the Smithsonian Institution. He could talk rocks with all of them.

In recent years, he seems to have become increasingly fascinated with meteorite. This brooch of Moldavite and pearl recently went on display in Out of this World! Jewelry in the Space Age at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (through January 4, 2016).

But he is probably best-known for his replications of famous diamonds. As Hatleberg himself puts it, he’s a counterfeiter, but he does it on the up and up. It’s probably what pays the rent on his Upper East Side apartment. Clients, including international jet setters as well as the Smithsonian and British Museum, say he’s among the best in the world.

But he is probably best-known for his replications of famous diamonds. As Hatleberg himself puts it, he’s a counterfeiter, but he does it on the up and up. It’s probably what pays the rent on his Upper East Side apartment. Clients, including international jet setters as well as the Smithsonian and British Museum, say he’s among the best in the world.

“I prefer to think of what I do as reverse engineering,” Hatleberg says. “But at the end of the day, what I’m doing is counterfeiting.” His forte is replicating diamonds in cubic zirconia, starting with the embedded flaws and working backward to the finished product. Among his proudest accomplishments is the replica he produced of the Kor-i-Noor, prize of the British Crown Jewels.

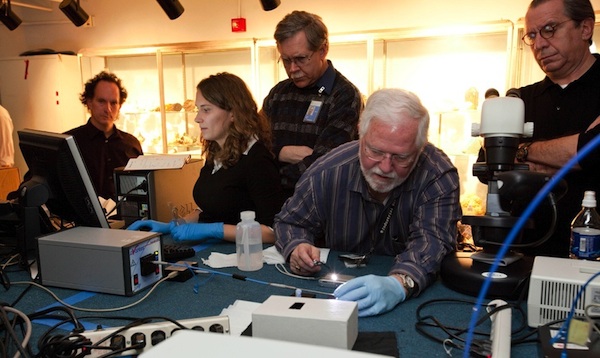

When we last spoke, Hatleberg was in the process of replicating the Hope Diamond for the Smithsonian from a mold he had made 19 years earlier. You can find the chocolate version in the gift shop at the Smithsonian.

When we last spoke, Hatleberg was in the process of replicating the Hope Diamond for the Smithsonian from a mold he had made 19 years earlier. You can find the chocolate version in the gift shop at the Smithsonian.

While it takes him three to four months to replicate most diamonds, the world’s most famous can take a lifetime. Hatleberg made a mold of the Hope back in 1989, but was only hired to create a replica for its 50th anniversary seven years ago.

With the Koh-i-noor, it took 13 years to get permission to make it.

What he wanted was to make a replica of the original Kohinoor, before it was recut and reduced from 186 carats to 108. According to Ian Balfour, author of Famous Diamonds, the book Hatleberg calls “his bible,” trustees of the British Museum had made a mold of the original back in 1851. “It wasn’t just for posterity, but also a study for scholars and artists,” Hatleberg explains.

In 1992, he went to London, determined to find the cast “in the bowels of the museum” – and he did, dated and inscribed. “It was a gem cutter’s dream.”

When the replica was finally commissioned for a big diamond exhibition at the Natural History Museum of London, he had only six months to cut it. The result was unveiled in 2005.

“Doing this means I’ve had the great privilege of access to these diamonds,” Hatleberg says. “I only work from the original.”

Diamond counterfeiting is nothing new, he insists, and not necessarily criminal. “People have had copies of diamonds since diamonds began,” he says. “I only make replicas for the owner or guardian. They use them to protect the stone in one form or another – the insurance, security, display, promotion. In the past, people have tried to kidnap owners for their diamonds. They were able to give them replicas instead.”

Related products