Thomas Mann made his reputation in the early ‘70s as a pioneer of the art jewelry movement. He grew up in western Pennsylvania and began making jewelry to pay for college, where he studied theatre set design. Inspired by Joseph Cornell’s boxes and the German goldsmith Herman Junger, Mann began applying the assemblage techniques of the Dada, Surrealist and Cubist movements to jewelry.

Caught up in the rebellious idealism of the era, he declared precious materials off-limits and experimented instead with alternative metals like brass, nickel and bronze, which he chased with whimsical patterns and combined with resin, acrylic, photographs and found objects—especially tiny machine parts from Cape Canaveral.

When Mann’s jewelry started gaining popularity in the late ‘70s, he made what he calls “a conscious decision to stay away from gold or precious gems. I approached it with a sort of socialist attitude: making the jewelry available to as many people as possible at a reasonable price. We were starving artists then. We didn’t care about having a successful business.” But as the demand for his work grew, so did his staff. “Having employees meant learning business skills which, quite frankly, I’d become an artist to avoid ever knowing.”

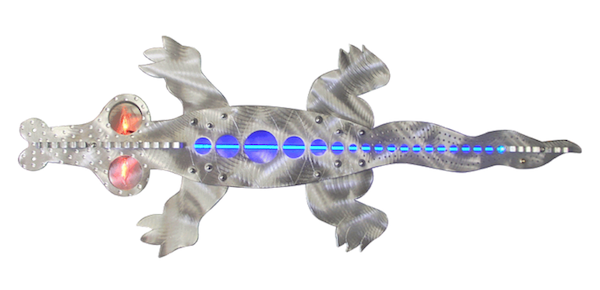

He incorporated hearts almost from the beginning as a sort of ironic counterpart to the industrial materials. In the early ‘80s, he dubbed the look Techno-Romantic and found himself with a jewelry world hit. At the peak of his success, Mann had 26 employees. Three decades later, the signature remains his bread and butter and is still widely imitated.

A New Orleans landmark since 1988, Mann’s Gallery I/O carries the work of dozens of artists, but he’s the big seller. For the most part, it’s the jewelry, not the sculpture or furniture, that people buy. They come looking for a little techno-romance.

As a businessman, Mann is grateful to be able to depend on continued demand for his original gimmick. As an artist, he chafes at the limitation. As he likes to say: “I’m happily stuck in Techno-Romantic but trying constantly to escape it. I can rework it for the rest of my life. It does still fascinate me—and I’m not tired of hearts.”

“They like you to change,” he says of his collectors, “they just don’t like you to change too much. I want people to prefer to buy things that represent my next level of creativity and thinking but they really want the hook to the artist personality that they know. It’s hard to get people to move into the avant garde with you.”

“They like you to change,” he says of his collectors, “they just don’t like you to change too much. I want people to prefer to buy things that represent my next level of creativity and thinking but they really want the hook to the artist personality that they know. It’s hard to get people to move into the avant garde with you.”

Don’t expect jewelry to be the first thing you see when you visit his gallery at 1812 Magazine Street. When I was there, large metal sculptures filled the front display windows. There wasn’t a piece of jewelry in sight when I first walked in, yet it was obvious who created these sculptures. They looked like giant versions of his jewelry—same themes, same images, even (what looked like) the same materials.

Although jewelry-making has supported him his entire adult life, Mann still resists the label of jewelry-maker. “I look at all the jewelry as prototypes for larger work. It lends credibility to the jewelry and it’s very fulfilling, but the jewelry produces much more income.”

“I’m not a jeweler by any stretch of the imagination,” Mann says. “I’m an artist working in the medium of jewelry, a sculptor who makes wearable, approachable objects.

“Frankly, a lot of the time, I design with not much wearability in mind. You don’t buy my jewelry to go with your outfits; you buy clothing to go with the jewelry. It’s created as an object of personal interest that attracts other people and produces an interactive experience. I tell my staff that our job is to create opportunities for people to interact. I see a personal mission to provide that.”

His staff also hears this motto on a regular basis: “We are manifesting the unmanifest for those who cannot manifest it for themselves. The objects we make are not about the commercial exchange that takes place but the energy exchange.” These are things he’s been saying for a long time.

“I really believe that’s why the American craft movement was so special and had such power. My generation of American craft artists became what we are not because we were on a mission to become artists or craftspeople. It was mostly a lifestyle and political decision. Everything I’m about is tied up in that. It’s the thing that fueled the growth of the American craft movement over the last 30 years.”

To see more of Thomas Mann’s jewelry and sculpture, visit his website.

Related posts:

Albert Paley: bodily ornamentation