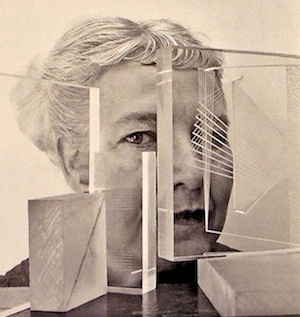

Margaret De Patta pioneered so many aspects of studio art jewelry we see now that many pieces she designed before World War II look like they could have been made yesterday – by an artistic visionary. A retrospective of her work closed at the Museum of Arts & Design in NYC last fall, but you can still get the hardcover catalog published last October.

Space Light Structure: The Jewelry of Margaret De Patta was one of my favorite acquisitions last year. I was knee-deep in research on De Patta when the book arrived and it was a thrill to flip through image after image. As studio jewelry goes, much of it seems so contemporary, it’s hard to remember how crazy it must have looked to the jewelry world when she was making it.

“Her jewelry was very fresh, very avant garde, very shocking to some people,” says Julie Muniz, one of the authors and co-curators of the exhibition.

De Patta was studying painting at the Art Students League in 1920s NYC when she got involved with jewelry design, and you can clearly see that influence of early Modern art in her jewelry. She made some fascinating kinetic pieces, with parts that swivel around to transform the design, and incorporated ordinary beach pebbles six decades before that would become trendy among art jewelers.

But the most beguiling jewels she made – or “wearable sculpture” as she referred to it – were the “opticuts” she designed with Bay Area lapidary Francis Sperison. De Patta did amazing things with rutilated quartz, designing metal frames to mirror the angles of the rutilations and using the quartz itself to create optical distortion.

Her experiments with jewelry began in 1929 with her own wedding ring. Unsatisfied with the ring she had commissioned, she asked a metalsmith to teach her how to do it. After working with him for two months, she still didn’t have what she wanted so she set out to find it on her own.

By then, she was deeply immersed in the Modernist movement and about to discover Bauhaus and constructivism. Those design approaches would influence her jewelry for the rest of her life, and the innovative ways she applied them impacted American studio jewelry on many levels.

“She was a pioneer far ahead of her time,” says MAD curator Ursula Ilsa Neuman, who helped organize the exhibition. Walk through the best juried craft shows today and you’ll find De Patta’s influence everywhere you look. At the time, however, her jewelry was embraced by a limited circle of collectors who recognized it as an extension of then cutting-edge Modern art.

“Her work was a statement,” says Julie Muniz, craft and decorative arts curator at Oakland Museum of California. “If you wore a De Patta piece, you were saying ‘I’m part of this group that believes this way.’”

De Patta had no interest in catering to popular demand. “Since she started as a painter, she saw what she was doing more as art than decoration,” Neuman says. “She really did not like what was happening in jewelry at that time. In the ‘30s, jewelry was either a leftover aesthetic of the Arts and Crafts movement or more commercial jewelry or really kitschy, sentimental trinkets.”

Along with a few other self-taught studio jewelry artists, such as Margret Craver, Art Smith and Ed Kramer, De Patta was unwittingly laying the groundwork for the post-war craft movement and what we now think of as American studio jewelry.

Self-taught or not, De Patta was an accomplished jeweler by the time she encountered Laszlo Moholy-Nager, Jewish leader of the constructivist movement in Germany, who had relocated to the U.S. to escape the Nazis. Bauhaus emphasized simplified forms and organic use of materials. Its form-follows-function philosophy fit her agenda and the innovative work Moholy-Nager was doing with movement and light, including in film and photography, inspired her to take her jewelry in a new direction.

Around the same time she began collaborating with Sperisen on the opticuts. “That period of 1939 to 1940 was when that great transformation occurred,” says Muniz. “That’s when she moved away from making simple pieces from metal sheets and rods to creating intricate designs in a more thoughtful way, using kinetics and reflective distortion.”

While she never incorporated precious gems or had any interest in the sparkle and flash of conventional faceting, De Patta became fascinated by quartz. She discovered she could produce something even more interesting than jewelry with moving parts. She could create the illusion of movement by playing with light reflection.

Clear and rutilated quartz proved the perfect medium. While she never ventured into faceting herself, she found her perfect partner in Sperisen, a skilled lapidary willing to follow wherever her imagination led. With Sperisen’s help, she began exploring the optical properties of quartz. She designed many of these pieces around what Sperisen referred to as his double-lens cut, with a curved top and criss-cross faceting that allowed light to enter the stone in a way that distorted the metal behind it.

These two quartz pendants are classic examples of that fruitful collaboration. One (above left) uses opposing facets to visually bend a metal rod behind the stone while perfectly merging it with the rutilations in the quartz. You have to look close to see what’s what – and then smile at the genius behind it.

The other (right) uses the facets on the quartz to visually shatter the metal rod behind it. If you think this looks cool in a photograph, you should see it up close. Move ever so slightly and it shatters again and again. Both pendants can be ogled at the Oakland Museum of California.

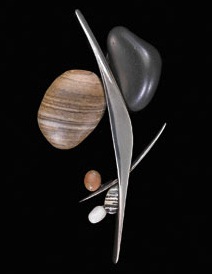

De Patta also began incorporating moving parts into her jewelry around this time. The biomorphic-shaped metal piece in the brooch (above right) pivots to reveal or partially cover stones and other components, allowing the pin to morph into several different designs.

With the help of a photographer, De Patta made time-lapse photographs of her kinetic pins in 1947, including Three Position Pin in Movement, demonstrating the jewelry’s mobility but also the direct influence of Moholy-Nager’s light-and-motion studies.

Her Modernist pieces look very much of their era, in a fine art sense. Artists such as Picasso, Ernst, and Braque were all dealing with similar biomorphic shapes and kinetic sculpture. In fact, Calder was making his own kinetic jewelry during the 1930s and 1940s.

But while Calder stuck with materials familiar to him from his larger works – base metals and found objects – De Patta was taking a more refined direction, literally, using high-grade metals and quartz cut in a very sophisticated way.

“She was one of the first to deal with that kinetic aspect,” Muniz says. “It all fit into the Bauhaus approach. Bauhaus was all about letting the material do what it wants to do, not forcing it into something that’s not its natural state.

“Thinking in terms of stones, what does quartz really want to do? Well, it’s inherently optical and so allowing it to be that is a very Bauhaus and constructivist principle.”

Except for quartz, De Patta seemed to prefer the texture and color of opaque stones such as coral, malachite, onyx, amber and moss agate.

Sometimes she made brooches from beach pebbles so they appeared scattered, the way stones appear when you walk along a beach. To further the illusion, she found ways to set them invisibly, so they appeared to float on the lapel.

In other pieces, she went the opposite direction, incorporating the earth tones and textures of those stones into geometric designs. Many of her mid-century pieces look like they were inspired more by Frank Lloyd Wright than the art or jewelry of that period.

patt

Soon after her death, studio jewelry took off. Her designs seem tame compared to much of the art jewelry produced then. Given the massive amount of studio jewelry produced in the last half century, amazingly few jewelry artists have managed to best her when it comes to kinetic jewelry, optical distortion, and truly wearable sculpture.

“She achieved the perfect trifecta of design,” says Muniz. “She managed to create jewelry that was beautiful and functional, but with a strong artistic statement behind it.”

(Adapted from an article I wrote for Lapidary Journal Jewelry Artist)

More women who paved the way:

Related products (Purchases made via links on this site don’t cost you extra but do put a couple bucks toward maintenance of this blog.):