It seems only natural that so many women design jewelry. After all, it’s primarily women who wear it—which may explain why female designers often bring a unique sensitivity to form-and-function. Sometimes it’s hard to remember that fifty years ago, jewelry was a male-dominated field, and a century ago, a gifted female designer counted herself lucky to work at all. If she did, it was usually behind the scenes, in a business run by men.

Jeanne Poiret Boivin worked behind the scenes, but ran the business herself. Her husband’s name pops up in almost every major jewelry auction, but the jewelry was almost always produced long after he died. What’s more, Jeanne Boivin chose to employ female designers and, in the process, developed a strong but feminine signature style under the Boivin name – and put a few other women on the map in the process.

Jeanne Poiret Boivin worked behind the scenes, but ran the business herself. Her husband’s name pops up in almost every major jewelry auction, but the jewelry was almost always produced long after he died. What’s more, Jeanne Boivin chose to employ female designers and, in the process, developed a strong but feminine signature style under the Boivin name – and put a few other women on the map in the process.

Today, I pay tribute to three of them, starting with the woman behind the man, whose name is on so many jewels he never saw.

[Update: This necklace, listed as a René Boivin necklace “after a design by Suzanne Belperron,” sold at Sotheby’s in April 2015 for $200,000. Six years later, Belperron’s name carries a lot more market value. She left the company a few years before this necklace was produced but had apparently designed it while employed there.]

Jeanne Poiret Boivin (1871-1959) lived in the shadow of two prominent Parisian designers, her brother Paul Poiret, a couturier, and her husband René Boivin. Jeanne had a great eye herself and proved a skilled businesswoman, managing the company by herself for its four most famous decades. Yet you’ll find only passing mention of her in most jewelry books.

René Boivin, a skilled goldsmith, founded the company in 1891, but his marriage to Jeanne Poiret two years later was pivotal for his business. Not only was she a skilled businesswoman, she had connections to the fashion world through her brother Paul Poiret, the most famous couturier in Paris at the time. You can see his influence on the jewelry his sister’s company produced, including a taste for exotic themes, colors and materials, and a passion for the Orient and Middle East.

“The House of René Boivin is a bit of a misnomer in my opinion,” jewelry expert Dianne Lewis Batista says. “René Boivin died in 1917 at the age of 53, at the height of his career. It was his wife who should be credited with much of the firm’s incredible fame. When he died she was in her forties and could have easily closed the shop, Batista adds, “but she decided the business should continue—a brave decision to make in 1917.”

She took over production as well as administration, employing others to draw her designs. “She knew how jewels should be worn, and like her brother, had a good sense of style,” Batista says. “Her work predated her time.”

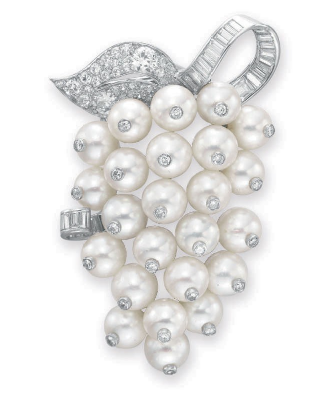

Boivin and the designers she employed favored abstract designs using closely-set gems and helped pioneer the use of rock crystal, wood and chalcedony in jewelry.

She launched the careers of a few very talented women, at least one of whom became a design legend. Suzanne Belperron was hired as a saleswoman at 21 then promoted to designer, but left in 1931, around the time Boivin hired designer Juliette Moutard, with whom she collaborated until her retirement.

This bracelet bearing the René Boivin mark, sold in December at Sotheby’s, looks like the work of Juliette Moutard, who had taken over from Belperron a few years earlier. You can see similarities in the jewelry these two designers produced in this transitional period – I compared similar bracelets here – but Moutard’s designs were more geometric and symmetrical.

Boivin’s daughter Germaine also became a designer at the firm in 1938, took over after her mother retired and eventually sold the company to Jacques Bernard, another Boivin designer, in 1976. (Asprey acquired the firm in 1991.) Thus, this jewelry firm, despite its male name, was run by women designers for 62 years.

Some maintain that working under her husband’s name allowed Jeanne Boivin to succeed in a male-dominated field. In his book on Boivin, François Kie writes: “Madame Boivin was always anxious to perpetuate the memory of her husband and professional use of his name. This only served for her as a kind of protection, permitting her to occupy a privileged position in the jewelry trade.”

More women who paved the way:

Related products: (Buying from links on this site doesn’t cost you extra but does add a few pennies to the maintenance of this blog.)