Ralph Esmerian, former owner of Fred Leighton, pleaded guilty last week to bankruptcy fraud, a tragic turn in a respected family business that took a century to build.

The Esmerians began like many jewelry businesses that relocated to New York in the early twentieth century, bringing their expertise in the old world European jewelry trade, then passing it on to the next generation. New York is full of successful third- and fourth-generation gem and jewelry dealers, but few rose as high as Esmerian.

Esmerian’s grandfather Paul worked as a lapidary in Constantinople before relocating to Paris in 1890. His son Raphael entered the business in 1919 and began pioneering the cutting and trading of colored gems as we know it. Raphael Esmerian (1903-1976) became a leading gem dealer in Europe and began traveling to New York to supply stones for Cartier.

This famous sapphire (right) provided a steady source of income for the Esmerian family over the years. Raphael Esmerian appraised the stone, then owned by John D. Rockefeller, Jr., more than once. In the 1940s, he helped Pierre Cartier recut it for a brooch. Then, in 1971, he bought it at auction himself for $170,000 and resold it.

The Rockefeller Sapphire appeared again at auction in 1980, four years after Raphael passed away, and it was his son Ralph Esmerian who bought it this time – for $1.5 million. He had it repolished to its current weight of 62 carats, set in a platinum ring, and sold. In 1988, Esmerian repurchased the stone at auction, this time for the world record price of $2,850,000, and sold it yet again.

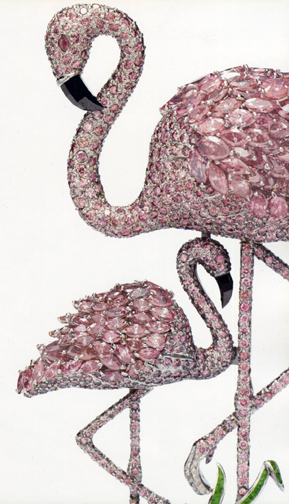

Over the next four decades, Esmerian built up the family business, joining forces with André Chervin at Carvin French to create jeweled creatures like the yellow-diamond butterfly (above) and pink-diamond flamingos (below). He also became a renowned collector of antique jewelry and folk art. It took decades to build his business and a collection worth many millions, but it all unraveled with breathtaking speed after he offered his personal collection as collateral to buy Fred Leighton.

Over the years, Esmerian acquired some beautiful jeweled objects, including several rare examples of Art Deco gem-set desk clocks and Art Nouveau jewelry like the brooch (above) designed by René Lalique. Many were offered in the Christie’s auction arranged by Merrill Lynch in 2008 to pay off some of Esmerian’s loan. Esmerian called it “a fire sale.”

Esmerian’s name was not mentioned in the catalog for that sale, titled “Rare Jewels and Gemstones: The Eye of a Collector,” but in its introduction, François Curiel, head of jewelry at Christie’s, praised the “subtle taste and eye” behind the collection.

At 6:05 pm, as the sale was about to begin, a call came in. Esmerian had convinced the court to declare Chapter 11 bankruptcy for Fred Leighton. Curiel announced from the podium that the sale would not take place. “We had a room full of 100 people, 150 more lined up to be on phone, and all the internet bidders waiting,” Curiel told me. “People were disappointed, disgusted, not happy. One guy who had flown in from Hong Kong especially to buy several pieces, left the room.”

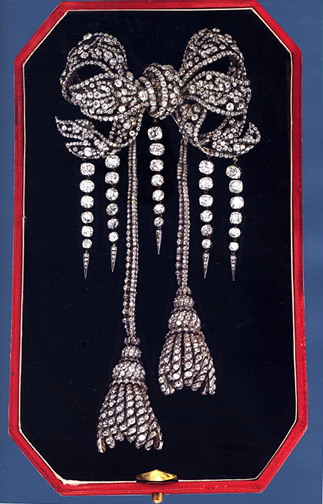

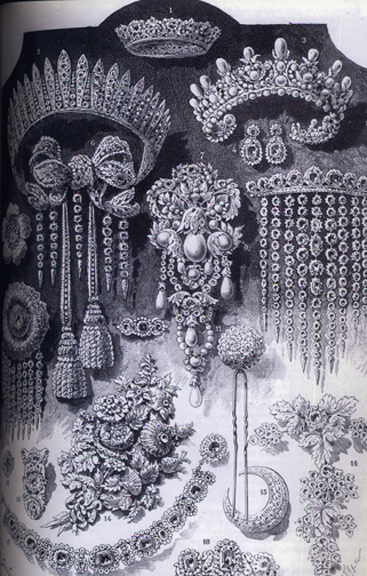

Curiel too was disappointed but all was not lost. The next morning, an agent from the Louvre called, inquiring about buying the most famous piece in the sale: the diamond bow brooch created for Empress Eugenie, wife of Napoléon III. It had been housed in the Louvre until 1887, when it was sold at public auction by order of the Third Republic, ending up in the possession of New York socialite Caroline Astor.

Christie’s now had to get approval from both Merrill Lynch and Esmerian to sell the brooch. Esmerian was not interested in selling to a private party but a museum was a different story. “He has always been very hot for museums and patrimony, conservation, public display,” Curiel told me at the time. “He likes museums. Exhibits have always been his thing.”

The Eugenie brooch, estimated at $4-6 thousand, sold to the Louvre for $10.5 million.

Everyone was happy. Merrill Lynch was happy to get twice the estimated price. Curiel, a French citizen, was happy to see a royal jewel from the French court returned to France, and Esmerian, a founder and former chairman of the Museum of American Folk Art, was happy the brooch went to the Louvre.

Negotiating the sale was complicated, given the now questionable ownership of the jewelry. “The judge could have blocked everything and held things up. After all, the brooch has been out of country for 121 years, what was another six months?” Curiel said. “But we managed to do it so quickly, the brooch ended up at the Louvre within a month.”

Now it appears Esmerian was doing a little private dealing of his own, putting up the same jewelry as collateral more than once (double-pledging), and quietly selling off choice pieces without notifying his lenders, including the now infamous $10 million diamond-and-ruby Endymion butterfly brooch by Boucheron.

Looking through the 2008 catalog of Esmerian’s treasures, I can’t help mourning the jewelry itself, now dispersed among personal collections around the world and hidden from view – except for the Eugenie brooch, which was, at long last, returned to the museum from whence it came.

I would have preferred to have it all waiting in a museum display case where I could come and admire it from time to time, along with the rest of the non-millionaire masses who love beautiful, sparkly, historical things.

I suspect Esmerian signed his collection over as collateral the way people pledge their homes, when the future looks rosy, never expecting someone to take him up on it. I think he felt proprietary towards those jewels, as collectors often do, and couldn’t resist trading them on his own, as he had done all his life. He may pay for that mistake by spending the rest of his life in jail.

Related posts:

Bankruptcy sale of Ralph Esmerian’s historic jewelry

Ralph Esmerian: rise and fall of a jewelry connoisseur

Christie’s sells Fred Leighton jewels

René Lalique: ultimate art jeweler

Related products:

(Buying via links here doesn’t cost extra but does put a couple bucks toward maintenance of this blog.)