Since ancient times, the chain has enjoyed a coveted place in jewelry. It represents eternal love and all the other good stuff about human connection: the eternity of the circle linked, without beginning or end, to other circles.

Of course, chains also represent all the bad parts of human connection like oppression, imprisonment and pain: chain gang, chain of fools, ball and chain. As we all know, one can quickly become the other.

In short, the chain is a perfect symbol for the paradox that is love. No wonder it’s been around so long—and altered so little. The oldest examples were found in ancient Babylonia (Iraq) in the Biblical city of Ur, where royal tombs hid magnificent gold jewelry dating to about 2500 B.C. Ur was the most powerful city-state in Mesopotamia at that time.

Among the treasures found in the tomb of Queen Puabi, buried in 2600 B.C. in the First Dynasty of Ur (Ancient Iraq) with her favorite jewelry and 52 attendants, were massive amounts of gold ornament, including this elaborate headdress (right) and lots of chains – often embellished with lapis and carnelian beads. She wore them as belts, necklaces, and, for important events, piled on enough gold to fell a small horse. Her chains were mainly variations on the perennial loop-in-loop, a technique that circulated throughout the Mediterranean, Western Asia and, eventually, the world.

Among the treasures found in the tomb of Queen Puabi, buried in 2600 B.C. in the First Dynasty of Ur (Ancient Iraq) with her favorite jewelry and 52 attendants, were massive amounts of gold ornament, including this elaborate headdress (right) and lots of chains – often embellished with lapis and carnelian beads. She wore them as belts, necklaces, and, for important events, piled on enough gold to fell a small horse. Her chains were mainly variations on the perennial loop-in-loop, a technique that circulated throughout the Mediterranean, Western Asia and, eventually, the world.

Chains have flourished ever since – for both sexes. Henry VIII presented heavy gold chains as signs of favor but kept the best for himself. Renaissance chains never looked as good as they did on the hunky Henry played by Jonathan Rhys Meyers in The Tudors.

A couple centuries later, chains were just as crucial to the well-dressed woman (the return of men’s chains was yet to come), only now they were long and delicate and held lorgnettes.

In the 1930s, Coco Chanel started a fad when she began to appear draped to the waist in gilt chains and fake pearls – a look everyone could afford, even the working class hit by the Depression.

Judging from a set that appeared at auction in 2000 (below), Chanel had her own chains customized with her favorite sayings, such as “Il faut aimer pour vivre et vivre pour aimer” (one must love to live and live to love).

The ancient symbolism of the chain was obviously not lost on Coco, gilt or no gilt.

A decade later, real gold chain shrank and expanded during the war, resembling tank treads, gas pipe links and bricks.

An early example is this gold-link bracelet by René Boivin, c. 1940, set with diamonds, which sold at Sotheby’s Geneva for $101,000 in November:

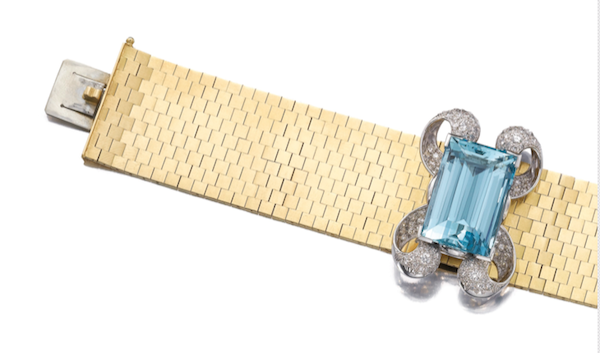

Later in the 1940s, we find a lot of brick-style bracelets, often set with citrine or aquamarine, by Van Cleef & Arpels – or this retro beauty by Gübelin, a flexible flattened brick-link bracelet with a removable gem-set clip:

Three decades later, long gold chains were back. But by the seventies, they weren’t piled on, Chanel-style.

They were chunky and sleek, like this 1970 Bulgari curb-link chain that sold for $23,750 at Sotheby’s New York last month.

You can find variations on all these themes in today’s fashion magazines – chains draped Chanel-like or bulky, industrial-looking cuffs and chokers – all reinventions of reinventions.

The chain is such a classic component of jewelry, yet designers and studio jewelers always find new ways to weave it .

And it never gets old.

Related content

Jewelry revivals: Egyptian style

Jewelry revivals: Cameo appearance