If you think building a career as a jewelry designer is challenging today, imagine what it was like 50 years ago, when the women’s movement was just catching fire – or a century ago when the suffragettes were battling in the streets for our right to vote.

Yet jewelry is an art form women have always had a natural affinity for. We’re the primary wearers, after all, and jewelry is often closely connected to fashion. Designing and making jewelry is a craft that requires a sharp eye and not much muscle. It can be done quietly behind closed doors. More often than not, throughout history, a man stood at those doors and ran the business.

There is probably much we don’t (and may never) know about the history of women jewelers. But we know women were influencing what other women wore as their crowning glory, at least as far back as the mid-19th century.

Here’s an overview of my long-running series “Women Who Paved the Way,” so you can scan that pivotal period in which female jewelers emerged from the shadows to shape jewelry design and the jewelry industry as we know it.

Click through at the end of each capsule to read my original profile, in its entirety, with more pretty pictures.

Charlotte Isabella Newman (1836-1920)

She paved the way for the women who paved the way. They called her Mrs. Newman.

Launching her career in the 1860s, when business and jewelry manufacture were male-only, Charlotte Newman produced sought-after jewels and, ultimately, ran her own shop on Savile Row. Even at the height of her career, with medals under her belt and men in her employ, she answered to her husband’s name and stamped her jewels “Mrs N.”

These days, that mark has become highly collectible, and is likely to get even more so.

By the time this pendant was made, Mrs. Newman had been producing jewelry for at least 25 years and running her own shop for six. Jewelry historians credit Charlotte Isabella Newman as the first important female studio jeweler. Active in London for the last four decades of the 19th century, she got her start working for jeweler John Brogden.

Charlotte Newman learned her trade at the Government Art School in South Kensington before becoming assistant to Brogden, who inherited a family business established in 1796. Some believe Mrs. Newman may have been producing jewelry before her own mark began to appear. When this amethyst bracelet bearing Brogden’s mark from the 1870s came up for sale at Sotheby’s London in 2007, the catalog description suggested Mrs. Newman may have had a hand in it.

A skilled goldsmith, Newman had a knack for producing exquisite jewels in a range of ancient styles, from Byzantine to Renaissance Revival, in a way that suited current tastes. Given the hunger for archeological revival jewelry in Victorian England, that made her a valuable asset.

She exhibited with Brogden in Paris in 1867 and in 1878, when he was awarded the Legion d’Honneur, and was even given a medal of honor of her own as a collaborator.

After Brogden’s death in 1884, she established her own business, retaining many of the craftsmen who had worked for him. Her business card read: “Mrs. Newman, Goldsmith and Court Jeweller, 10 Savile Row, London.”

“She ran a shop and had men working for her,” says Elyse Zorn Karlin, who co-curated Maker & Muse. “That was pretty unusual at the time.”

Jeanne Poiret Boivin (1871-1959)

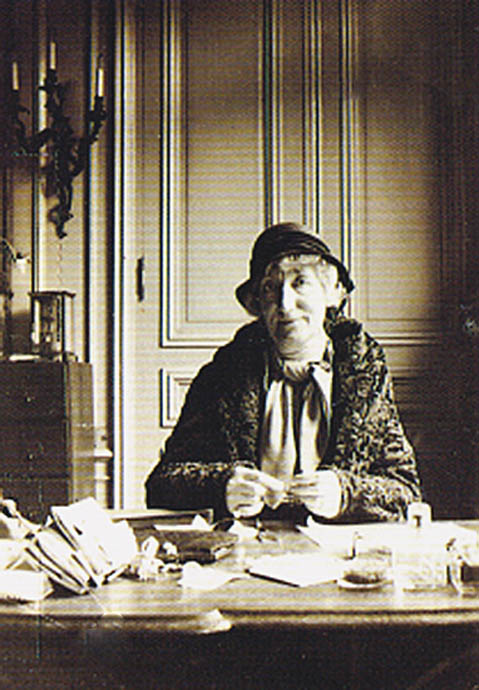

By the time the Parisian jewelry house of René Boivin became famous, René was long gone. It was his widow Jeanne Poiret Boivin who was running the show.

Jeanne Boivin chose to employ female designers and, in the process, developed a strong but feminine signature style under the Boivin name – and put a few other women on the map in the process.

She was the woman behind the man whose name is on so many jewels he never saw.

Jeanne Poiret Boivin lived in the shadow of two prominent Parisian designers, her brother Paul Poiret, a couturier, and husband René Boivin. Jeanne had a great eye herself and proved a skilled businesswoman, managing the company by herself for its four most famous decades.

René Boivin, a skilled goldsmith, founded the company in 1891, but his marriage to Jeanne Poiret two years later brought connections to the fashion world through her brother, Paul Poiret, the most famous couturier in Paris in the years leading up to WWI.

You can see a shared aesthetic in the jewelry his sister’s company produced, including a taste for exotic themes, colors and materials, a passion for the Orient and Middle East.

“The House of René Boivin is a bit of a misnomer in my opinion,” jewelry expert Dianne Lewis Batista says. “René Boivin died in 1917 at the age of 53, at the height of his career. It was his wife who should be credited with much of the firm’s incredible fame.”

Having lost her son and husband during the war, Jeanne Boivin had two young daughters to support. She had little choice but to take over the business, employing others to draw her designs. “She knew how jewels should be worn, and like her brother, had a good sense of style,” Batista says. “Her work predated her time.”

It’s almost impossible now to find a jewel made by the house of René Boivin while René Boivin lived. While he helped his wife lay the foundation for the business and its design aesthetic, the collectible brand we know today was created by Jeanne Boivin and the designers she employed, first Suzanne Belperron and then Juliette Moutard. Together, they created the distinctive look the house became famous for: bold, colorful jewels that moved beyond the harsh geometry of Deco.

Read more about Jeanne Boivin.

Jeanne Toussaint (1887–1978)

Jeanne Toussaint dramatically impacted jewelry design during her decades as director of Cartier’s luxury jewelry department, which she took over in 1933. Under her guidance in the late 1930s, Cartier began to move away from abstract Deco designs and into figurative work such as a series of black lacquer lady bugs and American Indian-head brooches.

She is also responsible for Cartier’s whimsical birds. Most famous is the caged bird that Cartier introduced in 1940, a symbol of resistance against the Nazi occupation, and the version that appeared in Cartier’s windows days after Paris was liberated: the bird poised for flight, cage door open.

“She felt that jewelry needed to be based on joy,” says jewelry dealer Dianne Lewis-Batista. “What better subject than birds?” Exotic parrots and flamingos were Toussaint’s forte, as were panthers—an image Cartier is known for to this day.

Nicknamed “the panther,” Toussaint obviously identified with this sleek predator. Her apartment was filled with their skins and she wore panther coats.The panther jewels struck a chord with other strong-willed females of the day. Among its wearers: Barbara Hutton, the Duchess of Agha Khan and the Duchess of Windsor (who owned both pieces pictured above).

Read more about Jeanne Toussaint.

Suzanne Belperron (1887-1983)

Suzanne Belperron honed her design skills during 14 years at the House of René Boivin. In 1933, wanting credit for her own designs, she left to work for gem dealer Bernard Herz, who had been supplying Boivin since 1912. He gave Belperron free rein to design anything she wanted under her own name. Together, they turned his firm and her reputation as a designer into an eponymous jewelry brand.

When Belperron left Boivin, she took not only her design experience, some say, but a few of the designs as well. Audrey Friedman, who collects and sells Belperron’s jewelry through her Primavera Gallery in Manhattan, has seen almost identical pieces, sometimes with Boivin’s marks, sometimes with Belperron’s. This may be partly because Juliette Moutard, who took her place as head designer, took a couple years to develop her own style.

Moutard did establish her own design aesthetic at René Boivin in the decades that followed. And so did Belperron, building an international reputation that continues to grow.

Signature Belperron pieces feature unusual gem material, often cut au cabochon or carved into fluid forms, elevated to high jewelry precious metals, sometimes diamonds. “Her talent in designing jewelry was in combining and manipulating materials,” says Friedman. “She was partial to non-precious material – agate, rock crystal, chalcedony and citrine – and made it the focus of a piece. Her work was very personal and very dramatic.”

After the occupation of Paris, Herz, a Jew, was arrested and taken to Auschwitz, where he died in 1943. When his son Jean returned to Paris two years later, having survived as a prisoner of war, Belperron took him on as a partner. Together, they ran Herz-Belperron until 1974.

Demand for Belperron jewels continues to grow. In the last couple decades, it’s really taken off. Suzanne Belperron is now one of the most avidly collected designers of the 20th century.

Read more about Suzanne Belperron.

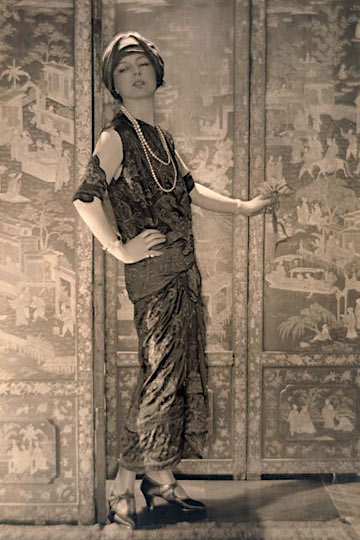

Elsa Schiaparelli (1890-1973)

Elsa Schiaparelli closed her shop in Paris almost six decades ago, yet her whimsical creations look as cutting edge as ever. Lady Gaga could wear her shoe hat on stage and no one would bat an eye.

Elsa Schiaparelli closed her shop in Paris almost six decades ago, yet her whimsical creations look as cutting edge as ever. Lady Gaga could wear her shoe hat on stage and no one would bat an eye.

Schiaparelli, or “Schiap,” as she was known (pronounced Skap), was well ahead of her time. Her shoe hats, designed from a sketch by Salvador Dalí, first appeared in her 1937/1938 collection. Schiaparelli shared Dali’s sense of humor and love of visual puns, as well as his desire to shock and entertain. He supplied the puns and iconic images; she managed to make them absurd and chic at the same time. Soon after these collaborations, Dalí began to seriously design his own jewelry.

Schiaparelli worked between 1920 and 1954, but her heyday was the decade before the war. She drew from all the popular art movements of her day, including Modernism, Futurism, Cubism, Deco, African art, but was particularly drawn to Surrealism. Along with Dalí, Jean Cocteau and Albert Giacometti collaborated on designs with her. Cecil Beaton and Man Ray photographed them. All considered her a friend and equal.

When Elsa Schiaparelli launched her first fashion craze in 1927—sweaters with trompe l’oeil bows—she had no training in clothing design. Two years later, she was outfitting the world’s most glamorous women and rocking fashion conventions with her bold colors and body-conscious designs. Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford, Marlene Dietrich, and Katharine Hepburn wore her form-fitting suits, mannish trousers, and cocky hats.

Elsa Schiaparelli also created some memorable costume jewelry and accessories, including the necklace (above) that made the wearer appear to have a parade of insects crawling around her throat. Her jewelry designs probably began with the fasteners she designed for her clothes from wood, china, celluloid, glass, crystal, amber, white jade, sealing wax – buttons shaped like shoelaces, snails, tops, padlocks, nuts and bolts, coffee beans, lollipops, peanuts, spoons, fruits and vegetables.

“She is responsible for the feeling of spontaneous youth that has crept into everything,” Vogue raved in 1935.

Read more about Elsa Schiaparelli.

Marianne Ostier (1902-1976)

Marianne Ostier was the primary designer behind Ostier, Inc., a jewelry firm she ran with her husband, Oliver Ostier in mid-century Manhattan. A winner of many prestigious diamond design awards, Ostier was known for intricately random mountings and organic textures that reflect her training as an artist.

Marianne Ostier was the primary designer behind Ostier, Inc., a jewelry firm she ran with her husband, Oliver Ostier in mid-century Manhattan. A winner of many prestigious diamond design awards, Ostier was known for intricately random mountings and organic textures that reflect her training as an artist.

Marianne Ostier studied at the Vienna Academy of Arts and Crafts and was a practicing painter and sculptor when she met her husband, known then as Otto Oesterreicher, a third-generation court jeweler in Austria. They came to the U.S. in 1938, after the Nazi annexation of Austria, and launched a jewelry business under their new name.

Several Ostier jewels sold well above estimates at Sotheby’s last year, including a diamond tiara that fetched $225,000, made for European royalty before the war. It showcases both Ostier’s fluid way with diamonds and platinum, and the regal connections the Ostiers had when they landed state-side. Another diamond-and-platinum piece in that auction shows the designer 17 years later, at her Mid-Century Modern peak.

It was on American shores that Ostier developed a very different signature style, involving less symmetrical, more organic form – and an equally astonishing mastery of gold. Her dramatic “Voodoo” necklace of 18k gold fringe and cabochon emeralds, interspersed with diamond-set platinum, looks like very luxurious seaweed and must have been quite a party stopper when it debuted.

It was on American shores that Ostier developed a very different signature style, involving less symmetrical, more organic form – and an equally astonishing mastery of gold. Her dramatic “Voodoo” necklace of 18k gold fringe and cabochon emeralds, interspersed with diamond-set platinum, looks like very luxurious seaweed and must have been quite a party stopper when it debuted.

Read more about Marianne Ostier.

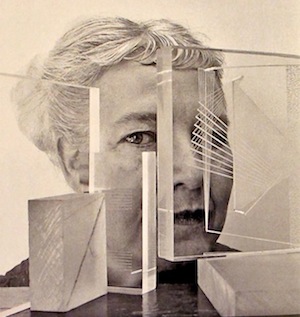

Margaret De Patta (1903-1964)

Margaret De Patta pioneered so many aspects of studio art jewelry we see now that many pieces she designed before World War II look like they could have been made yesterday – by an artistic visionary. If you weren’t lucky enough to see the recent retrospective of her work at the Museum of Arts & Design in NYC, you can still get the hardcover catalog published last October.

Margaret De Patta pioneered so many aspects of studio art jewelry we see now that many pieces she designed before World War II look like they could have been made yesterday – by an artistic visionary. If you weren’t lucky enough to see the recent retrospective of her work at the Museum of Arts & Design in NYC, you can still get the hardcover catalog published last October.

Space Light Structure: The Jewelry of Margaret De Patta was one of my favorite acquisitions that year. As studio jewelry goes, much of De Patta’s work seems so contemporary, it’s hard to remember how crazy it must have looked to the jewelry world when she was making it. “Her jewelry was very fresh, very avant garde, very shocking to some people,” says Julie Muniz, one of the authors and co-curators of the exhibition.

De Patta was studying painting at the Art Students League in 1920s NYC when she got involved with jewelry design, and you can clearly see that influence of early Modern art in her jewelry. She made some fascinating kinetic pieces, with parts that swivel around to transform the design, and incorporated ordinary beach pebbles six decades before that would become trendy among art jewelers.

But the most beguiling jewels she made – or “wearable sculpture” as she referred to it – were the “opticuts” she designed with Bay Area lapidary Francis Sperison. De Patta did amazing things with rutilated quartz, designing metal frames to mirror the angles of the rutilations and using the quartz itself to create optical distortion.

Read more about Margaret De Patta.

There are many more women who paved the way for the jewelry world as we know it. I will try to get to them as they surface at auction and exhibition. I think women will continue to play a major role in jewelry design. I’ve interviewed many talented male designers and makers over the years, but I’m meeting a lot more women these days.

This past year, I’ve watched a new generation reactivate an old struggle for equal rights, culminating in millions taking to the street around the world for the Women’s March in January. (I marched in Washington DC, with men and women.) We’ve come a long way but it’s becoming clear we’ve got a way to go. Today, let’s celebrate the brave and talented visionaries who got us this far.

Copyright ©Cathleen McCarthy. All rights reserved.

Recommended books

Jewelry by Suzanne Belperron: My Style is My Signature

Space Light Structure: The Jewelry of Margaret de Patta

Shocking: The Surreal World of Elsa Schiaparelli

This page contains affiliate links