Perhaps the most common form of classical revival jewelry is something most of us have been seeing all our lives: the cameo. Whose grandmother did not have one of those in her jewelry box? Mine brought hers over from Germany and wore it with pride, a treasured remnant of the family she left behind. It featured the typical classical female in silhouette, carved in shell.

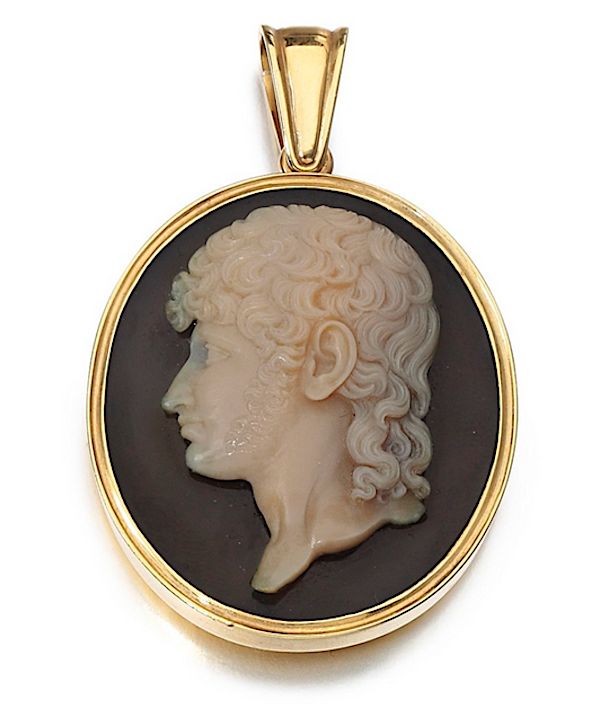

One cameo caused quite a stir at auction last month: an early 19th-century portrait carved in sardonyx of Joachim Murat, known in his day as “the dandy king.” Murat fought for Napoléon, married his sister, Caroline Bonaparte, and became King of Naples in 1808. Attributed to Filippo Rega, a carver favored by the Bonaportes, this cameo fetched nearly $45,000 at Sotheby’s London in 2018. After Napoléon’s fall, Murat fled to Corsica where he was tried for treason and sentenced to death. At his execution, he is said to have kissed a cameo of his wife, possibly also carved by Rega, before instructing the firing squad: “Straight to the heart, but spare the face.”

Here’s one a bit older: a Roman glass portrait of Emperor Tiberius, c. 1st century A.D., up for bids at Wednesday’s antiquities sale at Christie’s New York.

Here’s one a bit older: a Roman glass portrait of Emperor Tiberius, c. 1st century A.D., up for bids at Wednesday’s antiquities sale at Christie’s New York.

We’ve looked at the Egyptian Revival and Archaeological Revival jewelry in Past is Present: Revival Jewelry at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Let’s end with the case that traced miniature carved portraits from ancient rings to glass (18th-century England), coin (vintage Bulgari), and contemporary art jewelry.

During the Revival craze that took off in the 19th century, cameos weren’t just worn as a single brooch at the throat (the way my grandmother wore hers) but en masse. Revival jewelry was delicate but worn in abundance. Multiple-piece sets ruled – including, in the early classical style.

This beautifully carved shell cameo set from 1840 includes a necklace and no less than five brooches. “It’s interesting to wonder how that might have been worn,” says Emily Stoehrer, the MFA curator of jewelry who organized the exhibition. “Victorians wore a lot of jewelry. Their aesthetic was ‘more is more.’ They were also very creative in how they wore their jewelry. Brooches, for example, were worn in ways that were different from the way we think of brooches today.”

This suite features delicately modeled coral set in gold in the 1850s, designed with a Bacchus theme, complete with urns and grape vines.

The fashion for cameos held strong throughout the 19th century. But by 1890, when Mrs. Philip Newman designed this necklace (below) around a portrait of Elizabeth I, the fashion had moved from classical subjects into the Renaissance. I love that she chose an emerald frame to set off this agate cameo and managed to make the emerald resemble fabric swathed in diamonds.

Charlotte Newman worked for the London jeweler John Brogden, known for his Revivalist jewels, particularly Rennaissance Revival. But Brogden had died by the time she designed this piece, and his protégé, who signed her work Mrs. N, had opened her own shop on Savile Row. (You can learn more about Mrs. Newman here.)

In the collection of cameos in Boston, one stands out: a large carved shell mask by contemporary Japanes artist Shinji Nakaba. “His work, while clearly engaging with the past, is in a different scale and looks completely different than the 19th century originals,” Stoehrer says.

Nakaba shaped the mask so it resembles architectural ornament, a face carved in marble that’s been outside a while. Nakaba used the dark under layer of shell to create an illusion of streaking caused by centuries of rain. The eyes are almost gone – blind or weeping or both – but the expression on the face is serene. He calls this his “Peace” brooch.

Another mask that looks like it might have been carved in marble over a doorway, this pendant produced by Cartier in 1906 was designed around a Medusa head carved in white coral. It’s embellished with enamel, diamonds, and pearls and paired with a Byzantine bracelet featuring a Medusa cameo created much earlier.

“It shows there was this interest in reusing things from the past, like cameos, even in early history,” she says. “The level of detail the artists were able to get in all these cameos, carved shell and hardstone, is really extraordinary.”

Lest we forget the cameo tradition ties in to more than just carved hardstone, Stoehrer threw in a couple classical portraits in other materials.

Oldest cameo in the case dates to 1786 and is made not from gemstone but Wedgwood glass. It depicts a slave in chains in the style of the kneeling warrior of ancient Roman intaglios. That representation was chosen for a reason. Wedgwood, the glass manufactory based in Staffordshire, England, designed the medallion as part of the British movement to end the transatlantic slave trade.

Another throwback to the Greek gods shows up in the form of the ancient coins in this necklace by Bulgari, designed in the 1980s as a tribute to the most macho of gods, Heracles.

In some ways, we’re not as far from the Victorian mentality as we like to think, Stoehrer says: “If you think about the progress of modernity, there is a lot of similarity between then and now. Today, we have this great advancement of digital technology and in the 19th century, you had the industrial revolution.

“In both cases, there was the speeding up of modern life and the loss of hand craftsmanship – and the artists’ struggle with that. There was a looking backwards happening in both cases, simultaneous with these great technological innovations.”