Yes, the Midas of the “golden touch,” the one we know from Greek mythology, actually lived. He ruled a kingdom called Phrygia in ancient Turkey, and it seems he had quite a sendoff.

In The Golden Age of King Midas, opening this weekend at the Penn Museum in Philadelphia, expect to find ancient jewels, lion heads on everything from bracelets to wine vessels, and lots of fibulae. That’s plural for fibula, and there are nearly two dozen on display. I checked it all out at the press preview and took lots of pictures for you.

Just as Egypt had a few Cleopatras, more than one King Midas existed in ancient Turkey. But the one featured in this exhibition was famous for the golden touch.

Penn’s museum of archaeology and anthropology boasts many extraordinary ancient gold jewels, collected over the last century in digs funded, in large part, by this university Ben Franklin helped found. This particular exhibition centers around a royal tomb discovered in 1957, believed to be that of Midas or his father, and dating to 740-700 BC. Lots of jewelry was found, including a massive cache of fibulae at the head of the mummified king.

Ironically, none of them were gold. There is, however, enough ancient gold eye candy on display to keep us from being disappointed by a title with “golden” in it. These, for example, caught my eye at the press preview – found in other royal tombs of Ancient Turkey and dating a couple centuries after Midas.

All were made in Turkey a couple centuries later, unearthed in other tombs. Ironically, the famous golden-touch king had very little gold in his tomb. In fact, Aristotle claimed Midas died of starvation resulting from his “vain prayer” for the golden touch.

Most of the jewelry found in the king’s tomb was of bronze, as were bracelets found in other royal tombs of Ancient Turkey.

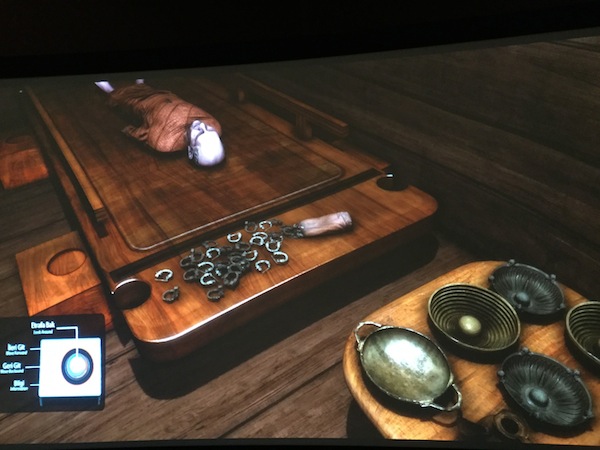

By far the most fascinating thing for jewelry nerds like myself, a huge number of fibulae – 182 of them! – were left with the king. Perhaps as a sort of “calling card,” as one museum spokesperson put it, by those paying tribute to the king at his burial. Each one is unique, as though custom-made for the wearer.

Fibulae on display include rare examples (above center) of double closures with removable shields. “These double-pinned fibulae – large, heavy, and with several component parts – are masterpieces of Phrygian bronze-working,” says Gareth Darbyshire, Gordion archivist at Penn Museum. “They were regalia reserved for the highest-ranking elite.”

Fibulae on display include rare examples (above center) of double closures with removable shields. “These double-pinned fibulae – large, heavy, and with several component parts – are masterpieces of Phrygian bronze-working,” says Gareth Darbyshire, Gordion archivist at Penn Museum. “They were regalia reserved for the highest-ranking elite.”

Albert Paley made funky art fibulae in the 1960s. A couple decades later, Joel Arthur Rosenthal produced bejeweled fibula brooches that now sell for big bucks. But this (above) is what fibulae looked like in the days of King Midas – sturdy, elaborate hardware used to hold garments together.

This is a rare opportunity to see the range of design and sophistication of metalwork produced in ancient Turkey, especially the kingdom where Midas and his father, Gordius (of Gordion knot fame), ruled.

Typically, the pin tip of the original fibula fastens into a decorated claw-like catch or hook situated at either end of the brooch. Fibulae were worn either singly or in pairs. Normally made in bronze, they were prestigious items that required great skill to manufacture. A few are known in precious metals – gold, electrum, or silver.

Most of the 182 fibulae found with (what Penn scholars believe was) King Midas, were stored in a cloth bag at his head. Others were on or beside him. Were they offerings to the king, the gods, or both? No one knows for sure.

Eighteen of that mother lode of fibulae are on display in The Golden Age of King Midas. A few others were found in other elite Phrygian tombs and in the citadel at Gordion. Phrygian fibulae were very distinctive in form. Since their styles changed over time, Darbyshire says, “the brooches are extremely useful as a dating tool for archaeologists.”

Also discovered, when they broke through the long buried tomb in 1957: evidence of a Bacchanalian feast to send off the king 2,700 years ago – the largest Iron Age drinking-set ever found, with bronze vats, jugs, and drinking-bowls. Penn scholars compared it to “an Irish wake.” At the press preview, an ancient-Turkish-style feast was served. There was even a special Dogfish Head ale brewed specially, with ingredients found in the wine vessels from Midas’ burial. Both menu and ale will to be served on weekends through the course of the exhibition.

What’s more, the museum has reconstructed an ancient Turkish tent, furnished as it might have looked like in Midas’s day. You can eat and drink inside the tent, sitting on pillows around low tables and pretend you’re in ancient Turkey. We did! If you go, plan to eat there. Both ale and food were delicious.

Wear appropriate jewels, of course. Belly dancing optional.

The Golden Touch of King Midas is on display at Penn Museum February 13 – November 27, 2016.