[Updated July 1, 2025]

René Lalique was born 150 years ago this month, yet even now many designers and jewelry artists still consider him the ultimate art jeweler. British designer Stephen Webster is one.

Lalique began anonymously enough, designing commercial jewelry for firms like Boucheron. But after he began ornamenting Sarah Bernhardt for the stage in 1894, he became a household name – at least in Paris.

It’s hard to imagine an ordinary woman wearing some of the jewelry Lalique created, although it’s fun to fantasize about turning up at a party wearing one of those massive tiaras shaped like peacocks or mermaids. In fact, much of lalique’s jewelry never served as such but was collected as art. Calouste Gulbenkian alone bought 145 pieces, and eventually displayed them in his museum in Lisbon.

There were a lot of talented Art Nouveau designers but Lalique was both a brilliant artist and a savvy businessman. At a time when few jewelry firms acknowledged individual designers, he signed every piece and made his presentation as artful as his product.

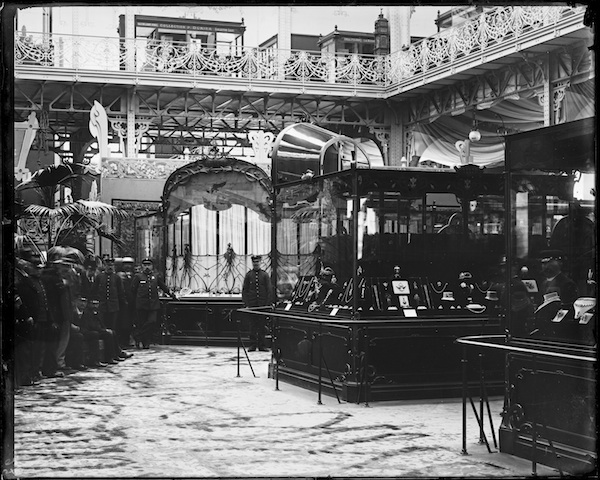

At salon and tradefair exhibits, he drew crowds not only with his jewelry but with the stage sets he designed to showcase it.

His booth at the 1900 Exposition, where he scored the Grand Prix, featured grillwork sculpted with winged female nudes and suspended black velvet bats – a reflection of the jewelry inside.

“You thought you were dreaming when you saw these beautiful things,” wrote jeweler Henri Vever of Lalique’s display. “A cockerel holding an enormous yellow diamond in its beak; a huge dragonfly with a woman’s head and diaphanous wings; enameled country scenes sparkling with diamond dew-drops; ornaments like pine cones.”

Many other designers were working with similar themes at the turn of the century – peacocks, bats and dragonflies, often merging with humans. Jewelry pictured in catalogs from that era was often downright creepy. “Some of the these people seem to be trying to be as bizarre as they could,” says Joan Rosasco, who coordinated the Jewels of Lalique exhibit that toured in 1998.

Lalique, on the other hand, could depict a woman emerging from the mouth of an insect and portray, instead of horror, a sense of metamorphosis and dreamlike mysticism. “Lalique always had good taste,” Rosasco says. “There was a poetry and elegance to his work.”

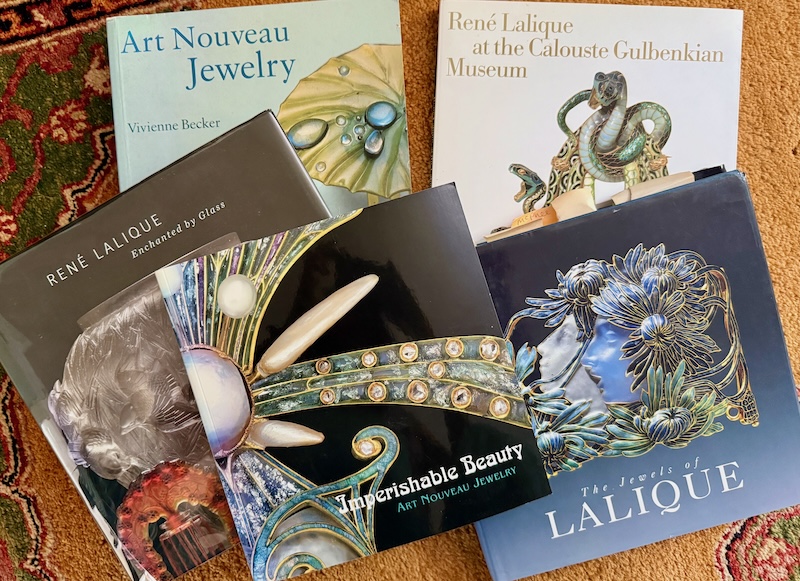

My favorite books on Lalique & Art Nouveau jewelry

René Lalique at the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum (2023)

Newest addition to my collection, I bought this in the museum shop of the Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon in 2023, after spending hours in the Lalique gallery. A beautiful visual record of the 82 jewels in that permanent collection and of a hundred non-wearable objects created by him. Best hit of Lalique I’ve had since …

Imperishable Beauty (2008)

Catalog for the exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, a beautifully photographed collection of Art Nouveau treasures from many jewelers of the era, many whom you’ve probably never heard of. With essays by Yvonne Markowitz and Elise Karlin and many gorgeous images of objects, jewels and other imagery from the era, this provides all the context most people need.

The Jewels of Lalique (1999)

Catalog for the 1998 exhibition at the Whitney, the moment I first fell under the spell of these jewels and the 1900 Paris Exposition where Art Nouveau became a global phenomenon and Lalque a household name, far and wide. This one is both well written and beautifully photographed. You can see by the ancient sticky notes popping out the top how often I’ve used this as reference.

Art Nouveau Jewelry (1998)

Thoroughly researched and beautifully written by Vivienne Becker, arguably the best text ever published on Art Nouveau jewelry, although not up to the visual standards of more recent books. This and Becker’s even older book specifically on Lalique jewelry (1987) are still worth buying for serious fans.

Related posts

Art Nouveau treasures by Philippe Wolfers