She paved the way for the women who paved the way. They called her Mrs. Newman.

Launching her career in the 1860s, when business and jewelry manufacture were male-only, Charlotte Newman produced sought-after jewels and, ultimately, ran her own shop on Savile Row. Even at the height of her career, with medals under her belt and men in her employ, she answered to her husband’s name and stamped her jewels “Mrs N.”

These days, that mark has become highly collectible, and is likely to get even more so.

A skilled goldsmith, Newman had a knack for producing exquisite jewels in a range of ancient styles, from Byzantine to Renaissance Revival, in a way that suited current tastes. Given the hunger for archeological revival jewelry in Victorian England, that made her a valuable asset.

Jewelry historians credit Charlotte Isabella Newman (1836-1920) as the first important female studio jeweler. Active in London for the last four decades of the 19th century, she got her start working for jeweler John Brogden.

You can find four examples of her work in Maker & Muse: Women and Early Twentieth Century Art Jewelry at the Driehaus Museum in Chicago until January 2016, and in the Maker & Muse book, including the pendant (above) and this aquamarine necklace from 1890.

By the time these were made, Newman had been producing jewelry for at least 25 years and running her own shop for six. She had exhibited with Brogden in Paris in 1867 and in 1878, when he was awarded the Legion d’Honneur, and was even given a medal of honor of her own as a collaborator.

By the time these were made, Newman had been producing jewelry for at least 25 years and running her own shop for six. She had exhibited with Brogden in Paris in 1867 and in 1878, when he was awarded the Legion d’Honneur, and was even given a medal of honor of her own as a collaborator.

After Brogden’s death in 1884, she established her own business, retaining many of the craftsmen who had worked for him. Her business card read: “Mrs. Newman, Goldsmith and Court Jeweller, 10 Savile Row, London.”

“She ran a shop and had men working for her,” says Elyse Zorn Karlin, who co-curated Maker & Muse. “That was pretty unusual at the time.”

While she was clearly working for profit, producing designs in popular demand at the time, Charlotte Newman had the creative spirit of an artist. A distinguishing feature of her jewelry: she rarely produced two pieces alike.

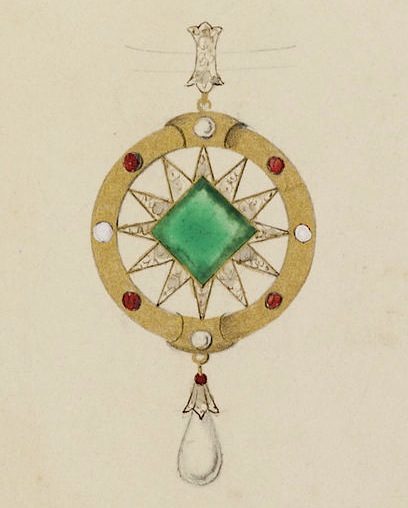

You’ll often find her mark on revival-style jewels popular in the final decades of that century, a style in which Brogden’s shop specialized. Here’s another 1890 piece by Newman, a pendant of gold, enamel, pearl, ruby, emerald and diamond, now in the permanent collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum. If you had a loupe to your eye and this pendant in your hand, you would see “Mrs. N” stamped on the back (right) and no doubt of her meticulous craftsmanship.  Mrs. Newman learned her trade at the Government Art School in South Kensington before becoming assistant to Brogden, who inherited a family business established in 1796. It’s unclear exactly when she went to work for him. Some believe she may have been producing jewelry before her own mark began to appear. When this amethyst bracelet bearing Brogden’s mark from the 1870s came up for sale at Sotheby’s London in 2007, the catalog description suggested Mrs. Newman may have had a hand in it.

Mrs. Newman learned her trade at the Government Art School in South Kensington before becoming assistant to Brogden, who inherited a family business established in 1796. It’s unclear exactly when she went to work for him. Some believe she may have been producing jewelry before her own mark began to appear. When this amethyst bracelet bearing Brogden’s mark from the 1870s came up for sale at Sotheby’s London in 2007, the catalog description suggested Mrs. Newman may have had a hand in it.  “By 1867, the taste for archaeological revival jewellery was widespread and John Brogden was a leading British antiquarian jeweller,” the Sotheby’s catalog description reads. “He was assisted from the 1860s by Charlotte Newman, a distinguished jeweller trained in the art of granulation, who’s fine workmanship possibly is illustrated in the bracelet offered here.”

“By 1867, the taste for archaeological revival jewellery was widespread and John Brogden was a leading British antiquarian jeweller,” the Sotheby’s catalog description reads. “He was assisted from the 1860s by Charlotte Newman, a distinguished jeweller trained in the art of granulation, who’s fine workmanship possibly is illustrated in the bracelet offered here.”

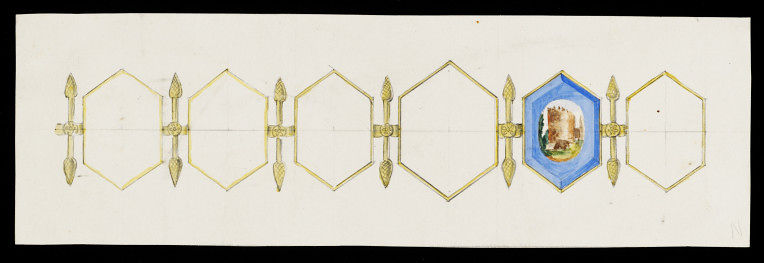

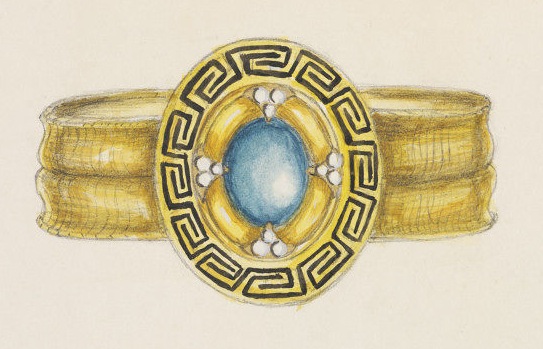

It’s possible in those early years, Brogden was sketching the design and handing the production over to his talented young assistant. Both Newman and Brogden were extremely prolific. The Victoria & Albert Museum has an album with 1,593 designs for jewelry and goldsmith’s work produced between 1848 to 1884. Seventy-four bear her signature, including these:

Pencil and watercolor drawings on card from the 1860s by artist/maker Charlotte Isabella Newman, from the prints & drawings collection at the Victoria & Albert Museum. Top to bottom:

Pencil and watercolor drawings on card from the 1860s by artist/maker Charlotte Isabella Newman, from the prints & drawings collection at the Victoria & Albert Museum. Top to bottom:

• Design for a gold bracelet with six hexagonal plates joined by spear-shaped middle sections, all blank except one showing an architectural depiction of a landscape with ruin

• Design for a gold bracelet with a medallion set with a turquoise, encircled by small pearls and a Greek wave pattern

• Design for a necklace pendant of a pearl, gold, rubies and square emerald set in a diamond star

In the notes on a sketch of Byzantine jewels bearing Newman’s signature, a Victoria & Albert curator wrote, “Such designs demonstrate the resourcefulness which made Newman indispensable to Brogden,” and noted Newman’s capacity to capture so many different styles “led to her becoming the first woman artist-jeweller in Victorian London.”

Often listed as “Mrs. Philip Newman,” Charlotte Newman was known in her day as simply “Mrs. Newman.” Signing her work “N” or “Mrs. N” may seem anti-feminist by today’s standards, but as dealer Diane Lewis-Batista pointed out to me years ago, the “Mrs.” in her mark “let people know immediately that it was designed by a woman.”

Topaz and enamel bracelet, 1895, signed Mrs N, auctioned at Bonhams London in November 2014

Topaz and enamel bracelet, 1895, signed Mrs N, auctioned at Bonhams London in November 2014

Viewed in that light, her mark could be seen as a way of not only claiming her designs for posterity, at a time when the jewelry trade was male-only, but challenging preconceptions even while honoring social convention.

“She’s really the first jeweler we know of who works under her own name,” says Karlin. For that alone, Karlin adds, “she led the way for other women.”

Photos courtesy Driehaus Museum, Victoria & Albert Museum, Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Bonhams

More women who paved the way: