A glorious retrospective of Cartier jewels opened Sunday at the Denver Art Museum, with 250 rare jewels produced between 1900 and 1975, heyday of that legendary jewelry house. Among the many pleasant surprises is a section called “Art of Smoking” that shows how the aristocratic fad for cigarette smoking began to impact luxury products at the turn of the century.

Most of the pieces in Brilliant: Cartier in the 20th Century (November 16 – March 15, 2015) come from private collections, most never (or almost never) displayed in public, many once owned by celebrated jewel hounds such as Elizabeth Taylor, the Duchess of Windsor, Princess Grace and Barbara Hutton and influential collectors like socialite Daisy Fellowes and Mexican entertainer Maria Félix, trendsetters of their time.

Cartier was also known for watches and elaborate art objects, including cigarette cases and “mystery clocks,” all well represented.

Let’s ogle some highlights, starting with the emerald- and diamond-studded crocodiles Maria Félix wore proudly at her throat in the seventies. Then I’ll share an outtake from a magazine interview I did with the show’s curator, Margaret Young-Sánchez.

Two Cartier Paris jewels from the Duchess of Windsor’s collection (above): Flamingo brooch, 1940, of platinum, gold, diamonds, emeralds, sapphires, rubies and Tiger lorgnette, 1954, of gold, black enamel, emeralds

Two Cartier Paris jewels from the Duchess of Windsor’s collection (above): Flamingo brooch, 1940, of platinum, gold, diamonds, emeralds, sapphires, rubies and Tiger lorgnette, 1954, of gold, black enamel, emeralds

Let’s talk about that necklace that’s pictured everywhere with the big juicy emerald and complex diamond and platinum setting. Was that a one-of-a-kind showpiece?

Margaret Young-Sánchez: It was. As far as I know, they never made anything similar to that. I believe the stone was supplied by the client in that case. It was a huge, spectacular thing but required a really strong piece of jewelry to hold it, so they went all the way in constructing a heavy, ornate, very dense mount to put it in, with an incredible number of diamonds.

It’s gorgeous.

MYS: Yeah. The Countess of Granard who owned it was an interesting woman, an American heiress who married an English earl and was a major client of Cartier. She bought a number of tiaras, some of which were spectacular.

You have a lot of tiaras in the exhibit, including an amazing laurel wreath with dangling jewel that belonged to Marie Bonaparte.

MYS: I think it was 1907 that Marie Bonaparte commissioned a whole suite of jewels for her wedding and that tiara was part of the ensemble, a spectacular piece. And tiaras – I really love tiaras. [laughs]

So do I [evidence here]. Did you try them on?

MYS: I tried on a number of the jewels.

That must have been fun.

MYS: Yes, yes. And having the chance to look at these objects in person, through a loupe, to see how they were constructed – that’s really interesting and informative too. To look at the front is spectacular, but you have no idea how intricate and complex the backs of them are. They’re sort of engineering works of art from the back.

Stomacher brooch, Cartier Paris, 1907, of platinum, sapphires, diamonds with detachable pendants

How does Cartier compare to Van Cleef and Arpels from the back? Those are also engineering feats.

MYS: Yes, and some of that is simply the French tradition of craftsmanship and jewelry making, France was really the world leader in that specialty. They prided themselves on it tremendously. There were workshops in Paris that supplied many of the jewelry houses. So you do get very high-quality craftsmanship in many of those brands as well but Cartier has always tried – and I think successfully – for the highest quality of workmanship.

What stood out when you were looking through the loupe?

MYS: I could see things like the different cuts of stones used in different eras. You could see how they were reusing stones. In many cases that’s because the clients had stones from other pieces of jewelry they were taking apart to get remade, so you might assume that all the stones from a particular necklace might be cut in the same way but they’re not.

So you might see rose-cut, brilliant-cut and old-mine-cut diamonds all in the same piece. They would be careful where they would decide to put a rose-cut diamond, for example, but they would use a mixture of those cuts, even round cuts, within a single piece of jewelry.

There’s so much to choose from with Cartier and there have been so many other Cartier exhibits. What were you going for with this one?

MYS: I wanted to emphasize Cartier’s internationalism and how that intersects with the increasing globalization of the 20th century, in terms of things like technology, communication, transportation, finance. I wanted to point out the intersection of the firm and their time, how they stayed in the forefront of their time.

One interesting example involves cigarettes. You have an entire section devoted to smoking (The Art of Smoking).

When did smoking become a theme at Cartier? I can imagine those cigarette cases on the set of a Fred Astaire/Ginger Rogers movie.

When did smoking become a theme at Cartier? I can imagine those cigarette cases on the set of a Fred Astaire/Ginger Rogers movie.

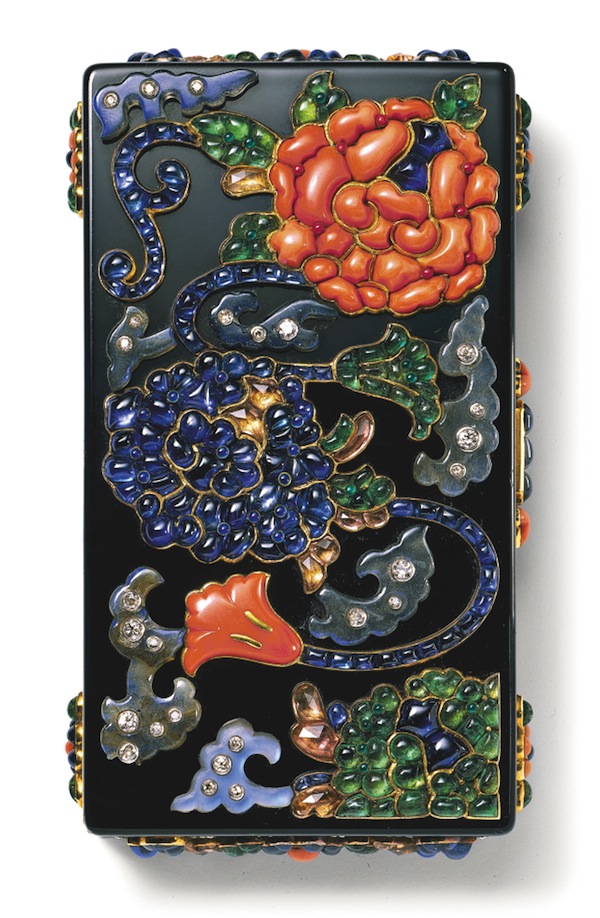

MYS: A lot of materials from the 1920s put the emphasis on Chinese style or Persian or Egyptian, but actually the style starts quite a bit earlier, right around the turn of the 20th century when cigarette smoking was just becoming popular among both men and women.

I guess if you were going to smoke, you had to look good doing it?

MYS: I think everybody wanted to look good doing it, of course, especially women. And I think that had something to do with why cigarettes became more fashionable. Cigars are very much associated with men and so are pipes. You’re not going to look good smoking either of those, but cigarettes are slimmer. You can look more elegant smoking a cigarette.

I think it also had to do with the fact that Russian women were smokers and, in high society, it didn’t have negative connotations in Russia. So there were wealthy Russians traveling to Paris and affecting fashion in the West.

Did Western society put that much stock in what the Russians were doing? We’re talking about pre-revolution, I guess, when the Russian aristocracy was still in the limelight.

MYS: Yes, and the Russians had incredibly elegant cigarette cases made out of things like onyx and gold and enamel and jadeite, really beautiful materials.

Well, that was Faberge’s era. Was Cartier catering to the same market?

MYS: They were, and they were competing. So in 1900, Faberge was the leading supplier to the Russian court but Cartier was very anxious to get a part of that market. Conversely Faberge was very intent on selling to western Europe. So in the 1900 exhibition, Faberge had a booth and were definitely trying to increase their buzz, and Cartier was trying to hold their own and also get in on the market that Faberge controlled.

Most people say the Paris exposition in 1925 launched Deco but you date it earlier, probably because Cartier was a bit ahead of their time where that’s concerned?

MYS: That’s exactly right. And it’s interesting when you look at their material from the first decade of the 20th century, you can see all the elements of art deco and they’re present by 1905, 1907. So they were already starting to simplify, introduce more abstract shapes, more geometry, more emphasis on color. I think art deco would have arrived earlier as a full-blown phenomenon than it did except for the first world war that brought everything to a stop and there was a hiatus. Then after WWI, everybody picked up where they left off and you get the full development of art deco.

That aquamarine brooch from 1937 seems to foreshadow what happened during the WWII, with the new emphasis on less-precious gems and white gold replacing platinum. Plus it was made at Cartier New York instead of Paris. Does this mark a point where focus shifted?

MYS: Well, the thirties marked a point where focus shifted and I think some of that has to do with the Depression. There was a greater emphasis during the Depression years on gemstones like citrine, aquamarine, amethyst, peridot. I think some of that was a matter of taste. People wanted something new and different and those materials let you make big pieces that made a visual statement. You couldn’t buy diamonds that size. So it was something really splashy but wouldn’t break the bank.

So it started as a Depression phenomenon, then with WWII did the focus shift more to the States?

MYS: Yes, the second world war affected everybody in Europe and in the U.S. too, of course, but Cartier in Paris and London were largely shut down. They didn’t close and they didn’t entirely stop production abut it was dramatically slowed. It was hard to get materials, workers were often in the army, and people didn’t have the money or really the desire to be purchasing as much at that time. So they kind of limped through or managed to hold out and survive during the war years, but it was a very difficult period.

Wasn’t it also the 1930s when the panther took off at Cartier, under the guidance of Jeanne Toussaint?

Wasn’t it also the 1930s when the panther took off at Cartier, under the guidance of Jeanne Toussaint?

Jeanne Toussaint developed the panther theme but she did not originate it. It actually goes back well before she started with the firm in the 1920s. She became head of jewelry in 1933 but their first panther items were made in 1913. What she emphasized were the more sculptural versions of the panther, like the Duchess of Windsor’s brooch.

So that story about her spotting a panther in Africa is a myth?

There is probably truth to it, in that she advocated and pushed that, and the story has resonance because of her interest and personality. They did call her “the panther” and that had to do with her personality.

Women associated with Cartier were a diverse group – Princess Grace, Elizabeth Taylor, the Duchess of Windsor, Daisy Fellowes, Maria Félix. Did the jewelry they commissioned reflect their personalities?

MYS: You can definitely see a personality when you go from one person to another in the exhibit. You can see their taste reflected. Cartier always produced a variety of different styles for different tastes, but these particular women helped to shape the taste of the times.

So Cartier worked with them to design and customize pieces?

MYS: Yes. That has always been the case with Cartier but these individuals often pushed the limits. Out of that group, probably Princess Grace was the most conservative in terms of her taste, but all the others had very strong tastes and were buying some of the most stylish materials.

Was it good for Cartier to be pushed that way?

MYS: I think it was undoubtedly good. In any company’s output, there will be some things that don’t stand the test of time. But there is a body of material that has survived from each of these women that has a level of quality and design that suggest that, yeah, it was very good for them – particularly the Duchess of Windsor and Daisy Fellowes. I think their patronage was really significant in shaping what Cartier started doing and their jewelry influenced a lot of women at the time.

******

Look for my feature on the Cartier exhibition in the winter issue of MILEU magazine.

I recommend the book from the exhibition – gorgeous, with essays by Margaret and several jewelry experts, including Martin Chapman and Janet Zapata. Well worth adding to your collection. You can find it here.

Related products